AuthorPeter Oakes is an experienced anti-financial crime, fintech and board director professional. Archives

January 2025

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

Copy of UK FCA letter on consumer duty to emoney and payments firms dated 21 February 2023 here at FintechUK.com

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

Friday 20th January 2023: Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) issued a Dear CEO letter to the fintech industries of electronic money institutions and payments institutions. The purpose is to reaffirm the CBI's supervisory expectations built on its supervisory experiences, both firm specific and sector wide, and enhance transparency around its approach to, and judgements around, regulation and supervision.

If you are looking to get authorised as an electronic money or payments institution in Ireland, contact us. We are working with a number of such applicants and we advise those already authorised on their on-going regulatory obligations, business models and strategy. See our Authorisation Page with links to useful Authorisation Guides. Busy start to the year with enquiries from UK, Asia and the US continuing to roll in about the benefits, opportunities and challenges of establishing a EEA regulated presence in Ireland, particularly for #emoney and #payments. While Ireland is in the top three of the final round, there remains stiff competition (so to speak) from two other leading jurisdictions. Thus it was good to see, , as I am sure others will agree, the Central Bank of Ireland most recent Dear CEO letter issued to emoney and payments institutions on Friday 20 January 2023 by Mary-Elizabeth McMunn, Director of Credit Institutions Supervision. It will help provide greater clarity not only to currently authorised emoney and payments firms, but also those in the authorisation pipeline and those thinking of filing in Ireland. It is a meaty document at 5,168 words across eleven (11) pages. Download a copy of the letter and additional relevant reading material here - https://complireg.com/blogs--insights/2023-dear-ceo-letter-re-supervisory-findings-and-expectations-for-payment-and-electronic-money-e-money-firms If you wish to get a quick understanding of the letter in terms of your regulatory obligations search the words 'we expect'. You will see those appear eleven (11) times too! Right now, best to mark in your calendar and work backwards, that an audit opinion on safeguarding, along with a Board response on the outcome of the audit, is to be submitted to the CBI by 31 July 2023. And it is not just a case of ringing your current external auditors and appointing them.

The purpose of the letter is to reaffirm the CBI's supervisory expectations built on its supervisory experiences, both firm specific and sector wide, and enhance transparency around our approach to, and judgements around, regulation and supervision. The breakdown of the letter is as follows: (1) Supervisory Approach for the Payment and E-Money Sector (provides wider and specific context to our supervisory approach). (2) Supervisory Findings (key findings from supervisory engagements over the last 12 months and actions the CBI expects firms to undertake) ➡ Safeguarding; ➡ Governance, Risk Management, Conduct and Culture; ➡ Business Model, Strategy and Financial Resilience; ➡ Operational Resilience and Outsourcing; ➡ Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism;

(3) Conclusion and Actions Required (CBI's expectation that this letter is provided to and discussed with your Board, and any areas requiring improvement that directly relate to your firm are actioned). Next Steps: Get in contact with Peter Oakes / CompliReg. Founded by the CBI's inaugural Director of Enforcement and AML/CFT Supervision & board director of payments, emoney and MiFID companies. Peter is also a former: FSA (now FCA) enforcement lawyer; senior officer (legal) at ASIC; and adviser to the deputy director of banking at SAMA. Further Reading: 10 December 2021: Authorisation Guidance and Supervisory Expectations for Payment and Electronic Money Firms (Central Bank of Ireland) 09 December 2021: Central Bank of Ireland Dear CEO Letter on Supervisory Expectations for Payment and Electronic Money (E-Money) Firms

Back to Blog

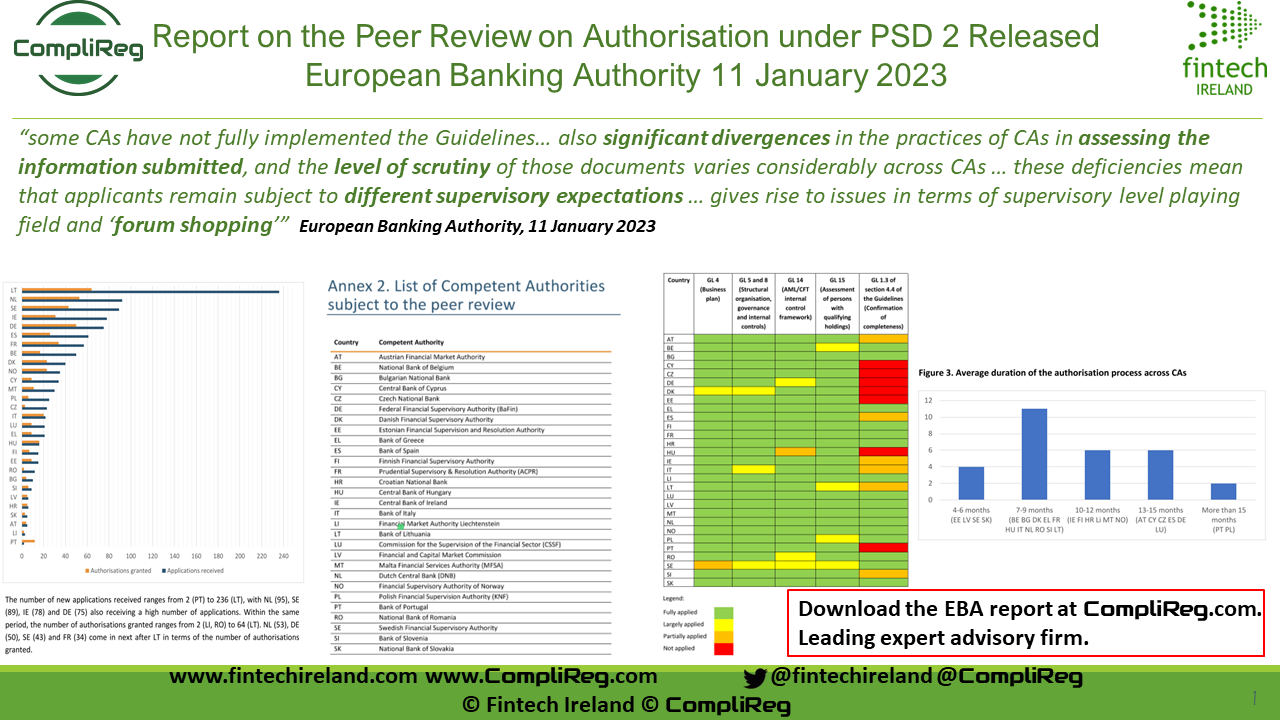

Report on the Peer Review on Authorisation under PSD 2 Released European Banking Authority11/1/2023 Are you looking for the Report on the Peer review on Authorisation under PSD2 released today by the European Banking Authority? Click here or the image above to download it in PDF format. If you are struggling with an application for an electronic money or payments institution authorisation in Europe, contact us here and/or complete the Authorisation/Licence Enquiry Form here. If you are looking at becoming authorised in Ireland as an emoney institution or payments institution check out Fintech Ireland's and CompliReg's authorisation guides here. What does the EBA peer review say?The report sets out the findings of the EBA’s peer review on the authorisation of #Payment Institutions (PIs) and #ElectronicMoney Institutions (EMIs). In executive summary format, the report says:

Some good supervisory practices observed by the EBASome good supervisory practices observed during the analysis that might be of benefit for other CAs to adopt.

Some recommendations identified by the EBAThe report expands on the recommendations included in the EBA’s response to the European Commission on the review of the PSD2 (EBA/Op/2022/06) and recommends that, as part of its ongoing PSD2 review process, the European Commission:

What are the objectives of the EBA report?The objectives of this report are to:

This report is also a partial fulfilment of the mandate conferred by the PSD2 on the EBA to review the Guidelines “on a regular basis and in any event at least every 3 years” (Article 5(5) PSD2). Which competent authorities are in scope?The peer review was performed by a Peer Review Committee of EBA and CA staff (see Annex 1 for the composition) and covered the CAs from all EU Member States and from two EEA States, as detailed in Annex 2. One EEA CA (IS) was not reviewed because it has only recently implemented the PSD2 and did not receive any application for the authorisation of PIs and EMIs in the period analysed (2019-2021). [CompliReg - not sure if IS is a typo, and should be 'SI' for Slovenia?] The Self-Assessment model adopted by the EBAThe analysis has been conducted based on the CAs’ responses to a self-assessment questionnaire (SAQ), which covered a three-year period from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2021. Where necessary, the PRC followed up with the CAs in writing seeking further clarifications and explanations. The PRC also conducted interviews with a subset of 10 CAs (BG, DK, ES, PL, PT, MT, NL, IT, LT and SE) to gain a better understanding of their supervisory practices. EBA Conclusion on timeliness of the authorisation processPage 51, para 171 "5. Conclusions and recommendations" sates: "With regard to the timeliness of the authorisation process, the review found that, while all CAs comply with the requirement in Article 12 PSD2 to take a decision on an application within 3 months from receiving a complete application, the average duration of the authorisation process varies significantly across MS, ranging from 4-6 months to +20 months. The main reason for this is the quality of applications and applicants’ timeliness in addressing the issues identified with the application. The PRC also identified a number of other reasons for these variations in duration across CAs, which include different timelines set out in national law and different procedural approaches adopted by CAs in the acceptance and assessment of applications." [CompliReg - no doubt, and there is merit here, many firms will struggle with the EBA's finding that "all CAs comply with the requirement in Article 12 PSD2 to take a decision on an application within 3 months from receiving a complete application".] The constitution of the 'peer review committee'?The Peer reviews were carried out by ad hoc peer review committees composed of staff from the EBA and members of competent authorities, and chaired by the EBA staff. This peer review was carried out by:

List of Competent Authorities subject to the peer review

Back to Blog

Reflections on DeFi, digital currencies and regulation - speech by Jon Cunliffe, Bank of England21/11/2022 I had intended today to talk about the work the Bank of England, is doing with the Treasury, the FCA on the regulation of crypto stablecoins and our work on a potential central bank digital currency in Sterling.

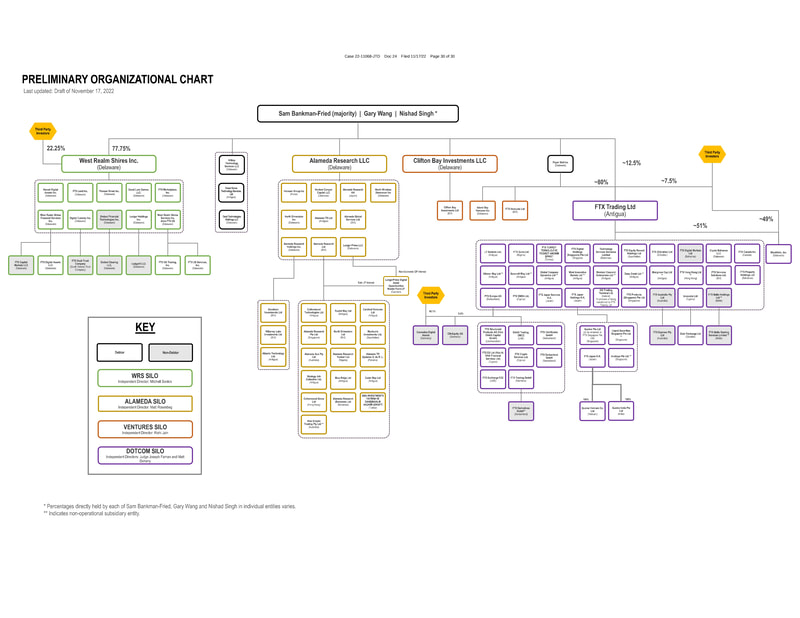

That remains the bulk of what I will talk about today. But between beginning to draft these remarks and delivering them today, we have seen what is probably the largest – and certainly the most spectacular – failure to date in the crypto ecosystem, by which of course I mean the collapse of the crypto trading platform FTX and most of its associated businesses. So I thought it might be worthwhile to start with a brief look at the FTX implosion to frame some of the points I intend to make on regulation of the use of crypto-related technologies to provide financial services and on why, as a central bank, we are actively exploring the issuance of a digitally native Pound sterling. Untangling exactly what happened at FTX will no doubt take a great deal of time, effort and investigation by the relevant authorities. For anyone interested in the scale of the challenge, I can only recommend a quick read of last week’s bankruptcy filing. But while we will not know in full how it happened for some time, there do appear to be some general themes that are very familiar to those who regulate and supervise conventional financial firms and financial instruments. The first are fundamental issues around how financial institutions should be organised, by which I mean their corporate structure, governance, internal controls and record keeping. Regardless of the financial service activity – be it banking, insurance, exchanges, clearing houses – regulation in the conventional financial sector imposes stringent/substantive requirements. Supervision aims to ensure that these are implemented. These requirements reflect the risks inherent in financial services – risks to the users, risks to other financial firms and risks more broadly to the financial system. Technology in and of itself does not change the need for transparency in corporate structures, governance, audit and systems and controls – for example to protect customers’ funds. In a similar vein, and to prevent conflicts of interest, regulation imposes requirements and constraints on the connections between a financial firm and its affiliates, while also requiring controllers to be fit and proper. In this respect, transparency in corporate structures and the relationships between them is the key foundation. The connections between activities carried out within the firm matter also. Lending, brokering, providing an exchange platform, clearing and settlement perform different economic functions that carry different risks. For financial market infrastructure firms, such as a central counterparty or an exchange or custody of assets (both/all of which activities FTX sought to undertake, the regulatory system and international standards in place aim to stop these important pieces of financial market infrastructure from taking on credit / liquidity / market risk beyond what is absolutely necessary to discharge their core functions. Where they happen within one group, regulation requires separate, independent governance, to ensure the risks inherent in each is properly managed.footnote[1] FTX, along with a number of other centralised crypto trading platforms, appear to operate as conglomerates, bundling products and functions within one firm. In conventional finance these functions are either separated into different entities or managed with tight controls and ring-fences. It is worth noting that this bundling appears to have been primarily organisational rather than technological – that is to say, the functions were offered by different parts of the FTX group but were not bundled in the sense of being run as one single piece of code performing multiple functions. I will return to the question of integration of functions in smart contracts later on. I have mentioned some familiar regulation issues around the organisation and governance of conventional financial firms. There appear, in the FTX case, also to be familiar issues around the financial instruments involved. Collateral performs a variety of vital function in financial services. It protects lending counterparties from credit risk. It can also serve as margin in clearing processes. The higher the credit quality and lower the volatility of assets used as collateral, the better suited it is to serving as assurance against risk. For this reason, there are stringent, material conditions on collateral that can accepted, for example, in central counterparty clearing. Unbacked cryptoassets are highly volatile, given that they have no intrinsic value. They are subject to runs and their value can change very quickly as we have seen in recent months. Moreover, a firm accepting its own unbacked crypto asset as collateral for loans and margin payments, as there are indications may have happened with FTX, creates extreme ‘wrong way’ risk – i.e. when the exposure to a counterparty increases together with the risk of the counterparty’s defaultfootnote[2]. Indeed, in the FTX case, there are indications that it could have been a run on its crypto coin, FTT, which triggered the collapse. Moreover protection of client funds is crucial. In many of these platforms the platform takes possession of the cryptographic keys and manages transactions on the ledger for a pool of assets. It is far from clear whether these practices deliver the assurance of either custody of assets in the conventional finance world or of a claim on the balance sheet in the way that occurs with accounts at a bank. ‘Crypto’ was born in unregulated space: indeed, part of the objectives of its early developers was to create a financial system outside regulation. While not yet of systemic scale, the crypto ecosystem has grown very rapidly in recent years and broadened to encompass a range of financial services. The experience of the past year has demonstrated that it is not a stable ecosystem. Part of this is because, its foundation is completely unbacked instruments of extreme volatility that can swing wildly in value. But part is also because the crypto institutions at the centre of the much of the system exist in largely unregulated space and are very prone to the risks that regulation in the conventional financial sector is designed to avoid. It is in part for this reason that, since September, the FCA has warned publically on FTX that “this firm may be providing financial services or products in the UK without our authorisation… you are unlikely to get your money back if things go wrong”footnote[3]. Some, of course, would argue that the answer is not proper regulation of the risks in centralised crypto platforms, like FTX, but rather the development of decentralised finance in which functions like lending, trading, clearing etc. take place through software protocols built on the permission-less blockchain. In such a world, it is effectively the ‘code’ that manages the risks rather than intermediaries. And indeed, there is some tentative and limited evidence that the failure of FTX has stimulated some transfer of activity to decentralised platforms. From the standpoint of a financial stability authority and a financial regulator, I have yet to be convinced that the risks inherent in finance can be effectively managed in this way. That scepticism is greater if the activity in question is the trading, lending, etc. of super volatile assets without intrinsic value. The robustness and resilience of the permission -less block chain has not been demonstrated at scale and over time. And some of the protocols themselves may carry risks – for example automatic liquidation of volatile collateral, no matter how rapid, does not remove the need for liquidity providers to avoid the amplification of fire sale dynamics. Moreover, it is not clear the extent to which these platforms are truly decentralised. Behind these protocols typically sit firms and stakeholders who derive revenue from their operations. Moreover it is often unclear who, in practice, controls the governance of the protocols. More generally, as with driverless cars, they are only as good as the rules, programmes and sensors which organise their operations. We would certainly need a great deal of assurance before such systems could be deployed at scale in finance. Against that background, the question – more pointed now, following the collapse of FTX - is whether we should bring the financial service activities and the entities that now populate the crypto world within the regulatory framework. And, if so, how? My answer to the first question is that we should continue to bring these activities and entities within regulation, for three reasons. First, and most obviously, the need to protect consumers/investors. Whether or not one thinks it is sensible to invest or trade in the highly speculative assets that make up most of the activity in the crypto world, investors should be able to do so in transparent, fair and robust marketplaces, with the protections that they would get in conventional finance. There will probably always be some who prefer – for a variety of reasons – to invest and trade in an unregulated, opaque world. But we should not push the majority who do not want those risks into that world because there is no regulated alternative. My second reason is the need to protect financial stability. While the crypto world, as was demonstrated during last year’s crypto winter and last week’s FTX implosion is not at present large enough or interconnected enough with mainstream finance to threaten the stability of the financial system, its links with mainstream finance have been developing rapidly. We should not wait until it is large and connected to develop the regulatory frameworks necessary to prevent a crypto shock that could have a much greater destabilising impact. The experience in other areas of digitalisation has demonstrated the difficulty of retrofitting regulation on new technologies and new business models after they have reached systemic scale. It is, of course, possible that neither of these two reasons - investor protection and protection against financial stability risk - will be relevant because the very instability and riskiness of the world of unregulated crypto finance, most recently demonstrated by FTX, will in the end ensure that the sector cannot grow. Indeed, some have argued for regulators grappling with the crypto world to keep it outside the regulatory framework to ensure that users’ ‘caveat emptor’ concerns prevents both growth and connection with mainstream financefootnote[4]. And that leads to my third reason. Forecasting the direction and pace of technological innovation is an even more uncertain game than economic forecasting. Promising technologies fall by the wayside; unexpected ones flourish. And technologies combine in ways that cannot be anticipated. But the technologies that have been pioneered and refined in the crypto world, such as tokenisation, encryption, distribution, atomic settlement and smart contracts, not only seem unlikely to go away as our everyday lives become more ‘digital’, but may well have the potential to improve efficiency, functionality and reduce risk in the financial system. A potential example of this is the integration of functions in ‘smart contracts’ that I mentioned earlier. A possible use case for such integration, which has been pioneered in the defi world is the combining the functions of trading, clearing and settlement of tokenised financial assets into a single, instantaneous contract, rather than being carried out in sequence by three separate institutions over a number of day. This, if applied to ‘real world’ assets, like equities, could offer a substantial improvement in the efficiency of financial market infrastructure and reduce risks by enabling instant settlement – T plus nowfootnote[5]. There are of course risks in such integration as I mentioned earlier, whether it happens organisationally or technologically. The Bank of England is working with the FCA and the Treasury to set up a regulatory ‘sand box’ for developers to explore whether and how those risks can be managed to the level of assurance we expect from the current systemfootnote[6] So my third reason for bringing the activities of the crypto world within the relevant regulatory frameworks is to foster innovation. This may appear counter intuitive to those who see regulation as opposed to innovation. But, as I have said before, ‘people do not fly in unsafe aeroplanes’. Innovation may start in unregulated spaces. But it will only be developed and adopted at scale within a framework that manages risks to existing standards. And by holding innovative approaches, using technological advance, to the same standards as existing approaches we can ensure that the benefits of new technology and new business models actually flow form innovation rather than from regulatory arbitrage. This in turn, determines the answer to the second question of ‘how’ regulation should be extended to these areas. The guiding principle should be ‘same risk, same regulatory outcome’. The starting point should be our existing regulatory frameworks – for investment products, for exchanges, for payments systems and other financial functions – and the level of assurance we require that the relevant risks have been managed. Technological change and different business models may mean we have to find new ways to deliver that assurance. We should be under no illusions that this will always be an easy process. For example, as I have said, it remains for me a very uncertain question whether use of the permission-less blockchain could deliver the necessary level of assurance for activities that are integral to the stability of the financial system. Our approach as regulators should be open – by which I mean we should be prepared to explore whether and if so how the necessary level of assurance – equal to that in conventional finance - could be attained. But we should also be firm that where it cannot, we are not prepared to see innovation at the cost of higher risk. This is very much the approach we are looking to take in the UK for the extension of the regulatory framework to the use of crypto technologies and business models in finance. The Financial Services and Markets Bill, currently in Parliament addresses the regulation of payment systems using “digital settlement assets” defined as “digital representations of value” – in other words digital tokens representing money. The objective is to extend the current Bank of England and FCA regulatory regimes for e-money and payment systems to cover the use ‘stablecoins’ for paymentsfootnote[7]. The powers in the Bill will extend not only to the systems for transferring such coins between parties to make payments, but to the issuance and storing of the coins. The Bank will have responsibility for such payment systems which are systemic or likely to become systemic. This will apply whether such systems exist to make payments for real things or for crypto assets should the latter activity become systemic in scale. We intend early next year to consult in detail the regulatory framework that will apply to such systemic payment systems and the services, like wallets, that accompany them. In doing so, we will be guided by the principle of ‘same risk, same regulatory outcome’ set out above. In the case of stablecoins used as money to make payments, the regulatory outcome has been expressed by the Financial Policy Committee of the Bank as an expectation that stablecoins used in systemic payment chains should meet standards equivalent to those expected of commercial bank money. And that's in terms of stability of value, robustness of legal claim and the ability to redeem at par in fiatfootnote[8]. Some of the likely foundational features of the regulatory regime on which we will consult are already clear. The FPC made clear last year that to deliver that regulatory outcome “regulatory safeguards will be needed for a non-bank systemic stablecoin to ensure that the coin issuance is fully backed with high quality and liquid assets, alongside loss absorbing capital as necessary, to compensate coinholders in the event that the stablecoin fails”footnote[9]. It also made clear that in the absence of deposit protection for coinholders, other elements of the regime would need to be strengthened to deliver the necessary level of assurance. The consultation will set out in more detail how the coinholders’ claims on the stablecoin issuer and wallets should be structured to deliver redemption at par in line with commercial bank money, how the backing assets should need to be managed to ensure they are always available to meet redemptions and, more generally the requirements for corporate structure, governance, accountability and transparency necessary to meet the standards we expect in other parts of the financial system that carry out the same functions. The FTX example underlines how important these aspects are. The legislation covers the use of crypto technologies for the payments function. The Treasury intends to consult in the near future on extending the investor protection, market integrity and other regulatory frameworks that cover the promotion and trading of financial products to activities and entities involving crypto assets. At present, in the UK, it is, to a large extent, only the anti-monetary laundering regulatory framework which applies to these activities and entities. Finally, let me turn to our work with the Treasury on central bank digital currency, or, to put it more plainly on the issuance by the Bank of England of a digitally native pound sterling. Our plan remains to issue a consultative report around the end of year setting out the next steps that we propose. Over the past few days, I have had a few comments both to the effect that the collapse of FTX shows that we need to get on and issue a digitally native pound – and to the effect that FTX shows that we do not need do so. My initial reaction to both points of view was that there really was no connection between FTX and our work on a digitally native, general purpose form of Bank of England money, for use by households and businesses in making payments. But on reflection, I think I understand the comments better. FTX in particular and the crypto ecosystem in general are emblematic of these new technologies and the possibility that they might revolutionise financial services and the forms that money takes in our economy. For some perhaps the lesson is that tokenisation and digitalisation of finance should not take place in unregulated space and, moreover, needs to be underpinned by a robust and reliable of digital settlement asset. For others, the message is perhaps that the crypto world and its technologies are a very long way from influencing, let alone changing, the way financial services, including payments, are delivered at scale in the real world. It is, as I said earlier, very difficult to predict which technologies will be successful and when and how they might begin to change the way we do things. The bursting of the dot.com bubble in the early years of this century did not herald the end of the development of internet commerce though it took longer than its original enthusiasts imagined and emerged in a very different form, dominated by big tech platforms. Our work on a digitally native pound is driven by the trends we now see both specifically in payments, including the reducing role of cash, and more generally in the increasing digitalisation of daily life. It is motivated by two primary concerns. First, that in a world in which new, tokenised forms of money emerge, enabled by new technology, we remain able to ensure that all forms of money that circulate in the UK are robust, interchangeable without loss of value and denominated our unit of account – the pound sterling. Physical cash plays a role in ensuring that, at present, all forms of commercial bank money in the UK have to be redeemable in cash - Bank of England money - on demand in cash and without loss of value. Given the trends away from physical cash, which cannot be used in an increasingly digital economy, and, potentially, towards new forms of tokenised money, a digital pound may be needed in future to fulfil the same function. Second, to ensure that there can be competition and innovation in the development of new functionalities using tokenised money. Given the network externalities around money and the likely cost of developing robust and risk managed tokenised money like stablecoins, it is possible that the development of digital settlement assets will converge on a few large players who will dominate and perhaps control innovation in payment services. We have seen a similar dynamic in the emergence of large internet platforms and marketplaces. A digital pound would provide a digital settlement asset available to a wide variety of private sector innovators and developers of payment services. The first concern is primarily for central banks, charged with ensuring the stability of money in the economy. The second is more of a concern for government. And of course there are other motivations, such as financial inclusion and resilience. I do not have the time to go into those in detail today, and, in any event, I do not wish to pre-empt the report on the next steps for this work that we and the Treasury intend to issue soon. But I do want to emphasise that this work, and any future decision to introduce a digitally native pound should not be seen in the context of the status quo but rather in the context how current trends in money, payments and technology might evolve. And above all, in this, as in the work on regulation that I discussed earlier, our aim is to ensure that innovation can take place but within a framework in which risks are properly managed and which safeguards the sustainability of such innovation. The events of last week provide a compelling demonstration of why that matters. Thank you. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, the Monetary Policy Committee or the Financial Policy Committee. I would like to thank Amy Lee, Teresa Cascino, Emma Butterworth, Katie Fortune, Bernat Gual-Ricart, Jenny Khosla, Grellan McGrath, Marilyne Tolle, Andrew Walters, Daniel Wright and Cormac Sullivan for their help in preparing the text.

Back to Blog

FTX Trading Ltd US Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware: Declaration by John J Ray III18/11/2022 Further to my post on Linkedin, here is access to a better quality image of the group structure of FTX. The image above should be of high quality. Otherwise see page 30 in the DECLARATION OF JOHN J. RAY III in support of Chapter 11 Petitions and First Day Pleadings.

The Guardian leads with "New FTX boss, who worked on Enron bankruptcy, condemns ‘unprecedented failure’"

Posted by: Peter Oakes, Founder of CompliReg a leading specialist governance, regulatory and compliance strategy firm. Peter established and led the Enforcement and AML/Supervision Directorate of the Central Bank of Ireland as its inaugural Assistant-Director General, then later Director of Enforcement and AML/CFT Supervision.

Back to Blog

Following the Permanent Representatives’ Committee meeting of 5 October 2022 which endorsed the final compromise text with a view to agreement, the Chair of the Committee (Edita Hrd) has written a letter and Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-assets, and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 (MiCA) to the Chair of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (Irene TINAGLI) saying:

"that, should the European Parliament adopt its position at first reading, in accordance with Article 294 paragraph 3 of the Treaty, in the form set out in the compromise package contained in the Annex to this letter (subject to revision by the legal linguists of both institutions), the Council would, in accordance with Article 294. paragraph 4 of the Treaty, approve the European Parliament's position and the act shall be adopted in the wording which corresponds to the European Parliament's position." The full legal text of the landmark legislation known as the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA), alongside a further law to reveal the identity of those making crypto payments. At a Wednesday meeting (5th October 2022), diplomats representing the bloc's member governments in the EU's Council signed off on the text of laws (see link above) which were the subject of political deals struck in June. MiCA introduces the first-ever licensing regime for crypto wallets and exchanges to operate across the bloc and imposes reserve requirements on stablecoins that are intended to avoid Terra-style collapses. A separate law on funds transfers requires wallet providers to check their customer's identity, in a bid to cut money laundering. See also CoinDesk Article here

Back to Blog

Revolut (finally) joins the UK Registered Cryptoasset Map Version 5.0 Monday 26th September 202226/9/2022 Fintech UK is looking to partner with registered / regulated (or soon to be) cryptoasset firms on building out a cryptoasset section on our website. If you are senior executive at a UK registered cryptoasset firm, please contact us here to discuss the proposed project. Also happy to hear from senior executives at businesses which support crypto firms to support the project. See our CRYPTO page for more information If you are are crypto firm seeking regulatory advice or director services, please contact CompliReg for assistance at the details appearing here and check out its VASP registration and other authorisation services here. Hope you like the Map (Version 5.0)! Welcome to the version 5.0 of Fintech UK's and CompliReg's (a leading provider of fintech consulting services to crypto asset firms) UK FCA registered Cryptoasset Firms Map.

There are now 38 registered Cryptoasset firms appearing on the Financial Conduct Authority's (FCA) website as at Tuesday 16th August 2022. Welcome to Revolut. The FCA register records Revolut Ltd registration effective 26th September 2022. Did you know that Martin Gilbert is Chairman of Revolut Ltd. He is the Chairman of AssetCo plc which is authorised by the FCA and former Chairman of Aberdeen Standard Investments. Revolut has quite a lot of firepower on its board generally speaking. Revolut has had quite a journey to be come a FCA registered cryptoasset firm. As far as we can tell, while other smaller and less resourced crypto firms were getting through the FCA process, Revolut Ltd sat on the Temporary Permission list since at least from December 2021. But all is well that ends well, right? As we continue to Map registered Cryptoasset firms, expect to see certain logos appear more than once as several brands will be registering several Cryptoasset firms for different purposes, such as - for example - services for (1) trading and (2) custody. An example of this is in fact Zodia. While Zodia Markets (UK) Limited was registered on 27 July 2022, its affiliate Zodia Custody Limited was registered effective 15 July 2021. At the time we released Version 1, there were 218 (thereabouts) unregistered cryptoasset business listed on the UK FCA's website that appear, to the FCA, to be carrying on cryptoasset activity, that are not registered with the FCA for anti-money laundering purposes. As of today (26 September 2022), that number is steady at 246. The firms thus far registered by the FCA include: 2020: Archax Ltd, Gemini Europe Ltd, Gemini Europe Services Ltd, Ziglu Limited, Digivault Limited, 2021: Fibermode Limited, Zodia Custody Limited, Ramp Swaps Limited, Solidi Ltd, Coinpass Limited, CoinJar UK Limited, Trustology Limited, Commercial Rapid Payment Technologies Limited, Iconomi Ltd, Skrill Limited, Paysafe Financial Services Limited, Crypto Facilities Ltd, Fidelity Digital Assets LTD, Payward Limited, Galaxy Digital UK Limited, BABB Platform Ltd, BCP Technologies Limited, Zumo Financial Services Limited, Baanx.com Ltd, Bottlepay Ltd, Genesis Custody Limited, Altalix Ltd, 2022: X Capital Group Limited, Enigma Securities Ltd, Light Technology Limited, eToro (UK) Ltd, Uphold Europe Limited, Wintermute Trading LTD, Rubicon Digital UK Limited, DRW Global Markets Ltd, Zodia Markets (UK) Limited, Foris DAX UK Ltd (aka Crypto.com) and Revolut Ltd. And of course the Revolut group is still pursing its much talked about bank authorisation in the UK. We are looking forward to seeing how many more will be registered before the end of the year. See Peter Oakes Linkedin blog - https://www.linkedin.com/posts/peteroakes_cryptoasset-fca-cryptoasset-activity-6980821130584412160-_63O?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop See Fintech UK blog - https://fintechuk.com/fintech-news/revolut-finally-joins-the-uk-registered-cryptoasset-map-version-50-monday-26th-september-2022 Further Reading: Version 1 of the Map and the Blog of 20 December 2021 - located here Version 2 of the Map and the Blog of 18 July 2022 - located here Version 3 of the Map and the Blog of 28 July 2022 - located here Version 4 of the Map and the Blog of 20 September 2022 - located here List of Unregistered Cryptoasset Businesses as at 20 September 2022 - located here

Back to Blog

ComplIReg: "The action will make the directors, both executive and non-executive at the relevant time of a prescribed contravention, of foreign incorporated financial services firms which operate in Ireland on a branch passported basis sit up and pay attention."Danske Bank A/S fined €1,820,000 and reprimanded by the Central Bank of Ireland for transaction monitoring failures in respect of anti-money laundering and terrorist financing systems. The fine would have been €2,600,000, but reduced by 30% to €1,820,000. So what you might think? Another bank, another AML/CTF sanction. But in this case it isn't an Irish incorporated bank but for the first time a penalty has been imposed on a financial institution which is incorporated and supervised outside of Ireland (i.e. in Denmark). It operated in Ireland on a passported branch basis. The same outcome could happen to any other firm which operate on a passport's branch basis. The action will make the directors, both executive and non-executive at the relevant time of a prescribed contravention, of foreign incorporated financial services firms which operate in Ireland on a branch passported basis sit up and pay attention. Such a regulatory action will need to be disclosed by them to regulators elsewhere. A regulatory enforcement action on a company where the directors may not be resident could damage their standing in, and income derived from, an overseas jurisdiction. In a little bit chest-beating, the Central Bank also announced that this 150th enforcement outcome takes the total fines it has imposed to just under €300 million. Which although is less than the total of the Ireland’s Data Protection Commissioner for a fraction of the number of its enforcement outcomes – not that it is a competition nor would anyone want it to be! In probably a fairly well known rumour circulating this past while, on 13 September 2022, the Central Bank of Ireland (the Central Bank) reprimanded and fined Danske Bank A/S, trading in Ireland as Danske Bank, €1,820,000 pursuant to its Administrative Sanctions Procedure for three breaches of the Criminal Justice (Money Laundering & Terrorist Financing) Act 2010, as amended (the CJA) for three failures by Danske to ensure that its automated transaction monitoring system monitored the transactions of certain categories of customers of its Irish branch, for a period of almost nine years, between 2010 and 2019. [This included a range of customers, including those categorised by Danske as banks, insurance, stockbrokers and specialised lending customers.] The three breaches, all admitted by Danske, comprised of failures by under the CJA relating to:

What led to the failures?

Below is a copy and paste from the remainder of the Central Bank of Ireland statement The Central Bank’s Director of Enforcement and Anti-Money Laundering, Seana Cunningham, said: “The importance of transaction monitoring in the global fight against money laundering and terrorist financing cannot be overstated. It is imperative that firms implement robust transaction monitoring controls which are appropriate to the money laundering risks present and the size, activities, and complexity of their business. These controls must be applied to all customers, irrespective of their risk rating, as they enable firms to detect unusual transactions or patterns of transactions and where required apply enhanced customer due diligence to determine whether the transactions are suspicious.

The Central Bank recognises that while firms may rely on automated solutions for transaction monitoring, they must ensure that systems employed for this purpose are appropriately monitored, and calibrated correctly to take account of the actual money laundering or terrorist financing risk to which the firm is exposed. In this case, the transaction monitoring system used by the Irish branch was a Danske group wide automated system that had applied historic data filters which operated to erroneously exclude certain categories of customers from being monitored for a period of almost nine years. This led to the serious breaches in this case. This case highlights the requirement for firms, including those operating in Ireland on a branch basis, to ensure that group systems, controls, policies and procedures are compatible with Irish legal requirements and to ensure that their governance framework and risk management measures operate effectively. These should be risk-based and proportionate, informed by firms’ business risk assessment of their money laundering and terrorist financing risk exposure. Danske became aware that its automated transaction monitoring system erroneously excluded certain categories of customers in May 2015 but failed to rectify it or notify the Irish branch or the Central Bank of this issue. It was only in October 2018 when the Irish branch identified the issue that steps were taken to rectify it, which were completed in March 2019. However, the Central Bank was not informed of the issue until February 2019. The failures to rectify the issue and to notify the Central Bank promptly are aggravating factors in this case. The Central Bank expects firms to bring failures to its attention at the earliest opportunity and to act expediently to address identified errors. The Central Bank will hold firms, including those operating in Ireland on a passporting basis, fully accountable where they fail to take such actions. Anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism compliance is, and will remain, a key priority for the Central Bank. This case demonstrates our willingness to pursue enforcement actions and impose sanctions where firms fail in their anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism compliance.” Background Danske is a credit institution incorporated in Denmark and authorised there by the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (the Danish FSA). It is the largest bank in Denmark serving personal, business, corporate and institutional clients and operates in a number of other countries via a branch network. Danske’s Irish branch operates on a ‘freedom of establishment’ basis i.e. because Danske is established and authorised in Denmark, it is entitled to ‘passport’ in to Ireland and establish a branch here. The Irish branch is not a separate legal entity to Danske, and it is for this reason that Danske is the named party in the enforcement action. Supervision of the Irish branch sits predominantly with the Danish FSA (as home regulator) but the Central Bank (as host country) regulates it for conduct of business rules and is responsible for supervision of compliance by Danske’s branch operations in Ireland with AML/CFT obligations under the CJA. Danske’s Irish branch predominantly provides banking services to large corporate and institutional customers including the public sector in Ireland. Consequently, transaction volumes through the Irish branch, including cross-border funds transfers, are substantial. The Irish branch utilises a group wide automated transaction monitoring system that is implemented and managed by Danske from Denmark. The Legislative Framework The CJA requires a credit and financial institution to monitor any business relationship that it has with a customer to the extent reasonably warranted by the risk of money laundering/terrorist financing (ML/TF). ‘Transaction Monitoring’ forms part of a broader system of interconnected elements that comprise a firm’s defence against ML/TF and is an important method which assists firms in identifying high risk situations which may require enhanced due diligence on a customer. Firms are also required to adopt and maintain a system of policies, procedures and controls in relation to AML/CFT, and to monitor compliance with those policies, procedures and controls. Such policies, procedures and controls include, inter alia, those dealing with the monitoring of transactions for the identification and scrutiny of any complex, large or unusual patterns of transactions. The Investigation The Central Bank’s investigation confirmed serious inadequacies within Danske’s automated transaction monitoring system. Historic filters were applied to Danske’s automated transaction monitoring system which erroneously excluded certain categories of customers from transaction monitoring. This led to Danske being in breach of certain obligations under the CJA which gave rise to the three breaches in this case (see below under Prescribed Contraventions for further detail). The investigation found that the exclusion of certain categories of customers from transaction monitoring was first identified in a May 2015 internal audit report. The May 2015 internal audit report also identified inadequacies with Danske’s transaction monitoring policies for certain categories of customers. However, these internal audit findings were not communicated by Danske to either its Irish branch or the Central Bank. Steps were only taken to monitor the transactions of these customers in October 2018 when the Irish branch became aware of the issue, which were completed by the end of March 2019. The Central Bank was not informed of this issue until February 2019. To illustrate the scale of the failure to monitor, it is estimated that, during the period from 2015 to 2019 when Danske was aware of the issue, 348,321 transactions, equating to approximately one in every forty or 2.43% of all transactions processed through the Irish branch were not monitored. Danske has confirmed to the Central Bank that by the end of March 2019 it had fully deactivated the erroneous historic filters which gave rise to the breaches in this case. Danske has also confirmed that by April 2020, it completed a third party review exercise for the period 2016 to 2019. Danske has advised that the outcome of the review showed that the risk of suspicious transactions amongst those examined was very low. Prescribed Contraventions The Central Bank's investigation identified three breaches of the CJA, as set out below. Breach by failure to conduct transaction monitoring Between 15 July 2010 and 31 March 2019 Danske breached sections 30B(1)(a), 35(3) and 36A(1) (as applicable) of the CJA by failing to monitor the transactions of certain categories of customers for money laundering and terrorist financing risk. The failure meant that the Irish branch was not in a position to:

Between 14 June 2013 and 31 March 2019 Danske breached section 39 of the CJA on the basis that by failing to conduct transaction monitoring on certain categories of customers, it did not take into consideration an important part of due diligence i.e. transaction monitoring data, which is necessary to identify and assess ML/TF risks specific to those customers and identify whether additional measures were required on these certain categories of customers. Breach in adopting ML/TF policies and procedures Between 15 July 2010 and 31 March 2019, Danske breached sections 54(1), 54(2) and 54(4) of the CJA on the basis that the policies, procedures and controls that were in place did not operate to identify the erroneous exclusion of certain categories of customers from transaction monitoring as set out above. The May 2015 internal audit report identified inadequacies with Danske’s transaction monitoring policies for certain categories of customers and Danske took some steps in 2015 to address this by introducing a new AML/CFT policy. Nonetheless, certain categories of customers continued to be excluded from transaction monitoring in the Irish branch. Penalty Decision Factors In deciding the appropriate penalty to impose, the Central Bank had regard to the Outline of the Administrative Sanctions Procedure, dated 2018 and the ASP Sanctions Guidance, dated November 2019. It considered the need to impose a level of penalty proportionate to the nature, seriousness and impact of the contraventions. The following particular factors are highlighted in this case: The Nature, Seriousness and Impact of the Contraventions Two of the breaches were ongoing for almost nine years, and the other was ongoing for almost six years. The breaches represent serious weaknesses in Danske’s internal AML/CFT controls. Monitoring transactions, ensuring that an important part of due diligence is taken into consideration to identify where additional measures are required, and having effective policies, procedure and controls are critical parts of a firm’s internal AML/CFT framework. Danske’s failures in this regard in respect of certain categories of customers that transacted through its Irish branch reveal serious weaknesses in these controls. From its May 2015 internal audit report, Danske became aware of the inadequacies in its transaction monitoring system, the nature of the ML/TF risks that they posed and that it was at risk of non-compliance with legal requirements. Despite this, Danske failed to take adequate action for almost four years or to inform the Irish branch of these internal audit findings. The breaches of the CJA after this point were reckless. The Central Bank considers that the breaches in this case represent a serious departure from the required standard. Two Aggravating Factors Failure to Report and Failure to Remediate promptly Danske was on notice of the inadequacies in its transaction monitoring system which erroneously excluded certain categories of customer from the time that they were uncovered in the May 2015 internal audit report but it did not report the matter to the Central Bank until February 2019, almost four years later. Furthermore, Danske continued to exclude certain categories of customers from transaction monitoring until March 2019. The Central Bank views both of these failures as particularly aggravating given the context of increased supervisory engagement it initiated in July 2018 with Danske following media reports of AML/CFT concerns in other jurisdictions in relation to Danske. Both of these failings are serious aggravating factors in this case. Other Considerations The following were also taken into consideration when determining the appropriate sanction:

Back to Blog

CompliReg, your first choice for regualtory authorisations, licences and registrations is proud to support Fintech UK and its endeavours to Map the FCA registered cryptoasset market in the UK. Fintech UK is looking to partner with registered / regulated (or soon to be) cryptoasset firms on building out a cryptoasset section on our website. If you are senior executive at a UK registered cryptoasset firm, please contact us here to discuss the proposed project. Also happy to hear from senior executives at businesses which support crypto firms to support the project. See our CRYPTO page for more information If you are are crypto firm seeking regulatory advice or director services, please contact CompliReg for assistance at the details appearing here and check out its VASP registration and other authorisation services here. Hope you like the Map (Version 4.0)! Welcome to the second edition (version 4.0) of Fintech UK's and CompliReg's (a leading provider of fintech consulting services to crypto asset firms) UK FCA registered Cryptoasset Firms Map.

There are now 37 registered Cryptoasset firms appearing on the Financial Conduct Authority's (FCA) website as at Tuesday 16th August 2022. Welcome to Crypto.com. The FCA register records Foris DAX UK LTD (aka Crypto.com) registration effective 16th August 2022. At the time Version 1.0 was released there were 218 (thereabouts) unregistered cryptoasset business listed on the UK FCA's website that appear, to the FCA, to be carrying on cryptoasset activity, that are not registered with the FCA for anti-money laundering purposes. As of today (20 September 2022), that number has decreased by one to 247. On both 18th and 28th July 2022 the figure was 248. Read more at Fintech UK on facts and figures about the cryptoasset firms appearing on Version 4.0. |

© CompliReg.com Dublin 2, Ireland ph +353 1 639 2971

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]