AuthorPeter Oakes is an experienced anti-financial crime, fintech and board director professional. Archives

January 2025

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

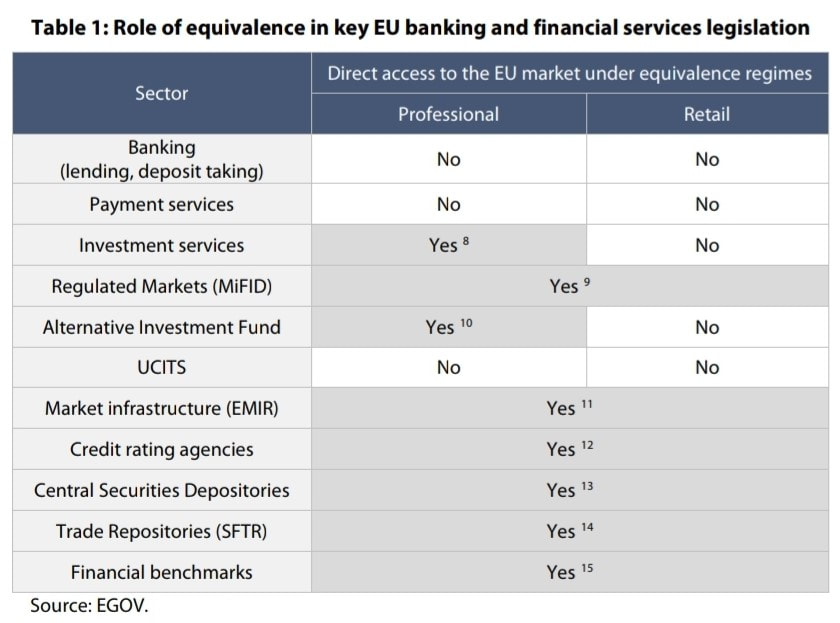

Some choice headlines in the papers about Brexit in the past week as we - according to Brexit Ireland's countdown to Brexit clock - just little more than 33 days before 11p.m. (UK time) on Thursday 31st December 2020 when the Brexit transition period ends with no deal on financial services in sight. This week sees the EU negotiating team returning to London after face-to-face talks came to end more than a week ago after Mr Bariner's team was hit by a case of Covid. They will be greeted by headiness such as: UK dismisses ‘derisory’ EU fishing offer ahead of last-ditch trade talks; Europe’s finance sector hits ‘peak uncertainty’ over Brexit; and The City braces for Brexit. There is no equivalence regime provided for within either EMD2 (electronic money institutions) or PSD2 (payments services institutions)! One thing we are still very surprised by is the many in #fintech, #techfin and indeed #finserv (and scarily their advisers) who think that recent news on 'equivalence' deals are applicable to all UK #finserv which passport across the European Union / EEA. The announcement on Monday 23rd November by the European Commission was simply and specifically about European regulators finalising a late change seeking to avoid chaos in £15tn of derivatives contracts held between UK and EU counterparties. Then on Wednesday 25th, they insisted outposts of EU banks in London would have to trade certain derivatives in the EU. Back in August 2020 the European Parliament reminded that "Equivalence decisions are a unilateral decision by the Commission. The Commission ultimately exercises its discretion as conferred upon it by the “empowerment” given in EU sectoral legislation.'' BUT MORE IMPORTANTLY "The Commission also enjoys discretion to withdraw equivalence decision. The equivalence frameworks in force do not provide as such specific procedures for monitoring, reviewing or amending equivalence decisions." There are no equivalence provisions in EU bank, payments nor electronic money directives, and the equivalence provision in MiFiD doesn't apply to retail investment services. See the below table on the 'Role of equivalence in key EU banking and financial services legislation' for confirmation. The upshot is that if you are a UK authorised payments institution or electronic money intuition, come Thursday 31st December 2020 when your ability to passport across the whole of European Economic Area comes to an end, so too does your business model unless you have obtained an authorisation in an EU/EEA state. There are are other options available but we'll leave that for another article. If you are a regulated fintech looking for a home post #brexit contact https://complireg.com/authorisations.html. Read our Fintech Authorisation Guides published jointly by CompliReg and Fintech Ireland on the authorisation process. And check out the 'Why Ireland for Fintech' brochure. Why Ireland for your regulated fintech?

“From January 1st, EU rules will apply to UK firms wishing to operate in the EU. UK firms will lose their financial passport: it’ll be anything but business as usual for them. This means they will have to adhere to individual home-state rules in each and every member state,” the official said. Further reading:

26 November 2020 - Move to EU or face disruption, City of London is warned

27 August 2019 - "Third country equivalence in EU banking and financial regulation"

29 July 2019 - Financial services: Commission sets out its equivalence policy with non-EU countries 12 July 2017 - "Third-country equivalence in EU banking legislation"

Back to Blog

Today, 17th November 2020, the Central Bank of Ireland released a Dear CEO Letter on "Thematic Inspections of Compliance by Regulated Financial Service Providers with their Obligations under the Fitness and Probity Regime". Readers are probably aware that the Central Bank issued a previous Dear CEO Letter on 8th April 2019 on "Compliance by Regulated Financial Service Providers with their Obligations under the Fitness and Probity Regime".

If you need assistance with understanding or implementing the requirements, please contact the Team at CompliReg.

What does the Dear CEO Letter of 17th November 2020 say? Background: The Central Bank undertook thematic onsite inspections across a sample of firms in the insurance and banking sectors [Ed- No reference to MiFID, payments, emoney, intermediaries nor the funds industry] in order to assess the level of compliance with the Fintess and Probity (F&P) requirements. This was on foot of its Dear CEO Letter on the topic of F&P back in April 2019. The inspections did not examine the fitness and probity of particular individuals, but rather evaluated the processes in place to manage compliance with the requirements of the F&P Regime. The inspections focused on the following areas:

The Central Bank towards the end of the letter reminds that the F&P Regime is a cornerstone of the regulatory framework in Ireland, applying not only to individuals but also firms. Firms must ensure that any individual who is engaged to carry out a CF role has the requisite fitness and probity to do so. The Central Bank’s Dear CEO letter of April 2019 emphasised the importance of compliance by firms and identified areas where compliance was inadequate. As is noted below and in the November 2020 letter, the Central Bank believes that the range of findings from thematic onsite inspections following the April 2009 letter "indicates that many firms do not have due regard to their obligations under the F&P Regime". The Central Bank is also concerned by the number of firms which did not take action, following the April 2019 letter, to perform a formal ‘gap analysis’ of their policies, processes and procedures. Its position seems clear "[i]t is wholly unacceptable that such shortcomings continue to exist in circumstances where the F&P Regime was introduced almost ten years ago." What did the Central Bank find?: In summary, the inspections highlighted a number of common issues and shortcomings, resulting in the release of the Dear CEO letter. The letter sets out key findings and observations from the inspections together with the expectations of the Central Bank, which it believes need to be brought to the attention of the wider financial services industry. Helpfully, the Central Bank also set examples of good practices which had been implemented in a number of firms (see Appendix 1 of the Dear CEO Letter November 2020 and set out below). A significant number of findings were identified in relation to the role of the Board, the conduct of due diligence and the outsourcing of CF roles. While not all of the issues outlined in the Dear CEO November 2020 letter arose in each firm inspected, the Central Bank reckons that they are representative of the findings across the sample of firms. What are the key points arising from the findings?: (a) role of the Board in the F&P Process:

(b) Conducting Due Diligence:

c) Outsourcing of Roles subject to the F&P Regime [Ed- the area of outsourcing is important for large, small, complex and non-complex firms alike]

d) Engagement with the Central Bank

e) Role of the Compliance Function

Conclusion of the Central Bank:

Appendix 1: Key Findings Identified by the Thematic Inspections a) Levels of awareness and understanding of the F&P Regime Role of the Board / Nomination Committee (“NomCo”) in Fitness and Probity Process 1. The level of awareness of fitness and probity obligations was weak throughout many of the firms, with Board awareness of its obligations particularly poor. 2. Board appointment procedures were generally not subject to the same level of scrutiny or formality as other CF and PCF appointments. In most cases, there was a lack of interview notes or suitability assessments available to support Board appointments. 3. In a number of instances there was no evidence of Board approval of the PCF appointment, Board approval of the appointment took place after approval by the Central Bank and/or there was no evidence of discussion or challenge by Board members of the proposed appointment. 4. Instances of the Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) screening potential Board candidates were noted in a small number of firms. This is inappropriate given the conflict of interests that arise as between the respective responsibilities of directors and the executive. 5. The quality of succession plans for the Board and executive team generally did not meet expectations. Anumber of these succession plans did not set out the skills, competencies and experience required for the various roles and/or how the proposed successor would demonstrate/acquire those. However, some firms had developed their own Board Skills Matrix, which set out the key areas of experience required. This matrix was used to identify gaps in the combined experience of the Board. Functional Responsibility for the F&P Regime 6. Management of the fitness and probity process varied significantly across the firms. Where there were clear, prescribed roles and responsibilities along with appropriate segregation of duties, the due diligence conducted in these firms was of a higher standard than those without clearly articulated and assigned responsibilities. 7. The quality of policies and procedures in relation to fitness and probity varied from firm to firm. Elements of good practice were observed in the form of ‘How To’ guides, establishment of Fitness & Probity Steering Committees, checklists, and clearly documented roles and responsibilities in relation to the fitness and probity process in the firm. However, good practice was not evident in most firms; the majority had disjointed processes that did not clearly outline the roles and responsibilities of the various functions performing fitness and probity related tasks. Analysis and Mapping of Roles 8. There were instances where no register of employees performing PCF or CF roles was maintained. In addition, the process of regular review of individuals whose role changed, resulting in their coming within the remit of the F&P Regime, was lacking. Good practices identified included a documented requirement to review the job description when a vacancy arises to determine if the role is CF or PCF in nature, and guidelines setting out the key principles and rationale for the general interpretation of the CFs across the firm. b) Conducting Due Diligence Initial Due Diligence 9. In the majority of the firms inspected, the initial due diligence undertaken was not sufficiently robust to evidence compliance with the requirements of the F&P Standards. Issues highlighted by the inspections included: a lack of evidence of academic qualifications; lack of references from previous employers; a notable absence of interview notes across the majority of firms inspected; and no evidence of a documented assessment as to the suitability of the candidate. 10. Issues were also identified in a number of instances with a lack of judgement searches, regulatory searches, directorship searches and adverse media searches, including adverse media searches regarding previous employers that could assist with identifying potential fitness and probity concerns to be examined further. 11. Firms assessed as performing better had defined processes in place for conducting initial due diligence, including documented policies and procedures; an understanding of the allocation of responsibilities among the various functions (e.g. Human Resources, Company Secretary and Compliance Function); performed due diligence searches and conducted and retained interview notes. Ongoing Due Diligence 12. Under Section 21 of the 2010 Act, firms are required to conduct due diligence on an ongoing basis to ensure that employees performing CFs continue to comply with the F&P Standards. 13. All firms had in place a requirement for each PCF and CF role holder to annually certify their compliance with the F&P Standards and their agreement to abide by the F&P Standards. An annual self-declaration by PCF and CF role holders is the minimum expected by the Central Bank. 14. However, the ongoing due diligence process in most firms is limited to the annual self-declaration. Firms should proactively conduct ongoing due diligence screening of staff to ensure there has been no change in circumstance that may affect the fitness or probity of the individual. In one firm they conducted ongoing due diligence searches on an annual basis for all PCF role holders and on a sample basis for CFs. c) Outsourcing of Roles subject to the F&P Regime 15. Where CF roles are outsourced to unregulated OSPs, the majority of firms had not, as part of their due diligence in appointing CF role holders, obtained the required documentation nor made any inquiries as to the OSP’s process for assessing fitness and probity. 16. Firms did not have a process whereby outsourcing arrangements were analysed to verify whether PCF or CF roles were being performed. This gives rise to the risk that relevant individuals at OSPs may not be identified and subjected to the F&P Standards. 17. In addition to obligations under the Central Bank’s F&P Regime, the Solvency II Regulations impose requirements on insurance firms with respect to the outsourcing of critical or important functions. Under these Regulations, firms are obliged to verify that all staff of the service provider who will be involved in providing the outsourced functions or activities are sufficiently qualified and reliable. There was generally a low awareness of Solvency II obligations in this regard and these had not been included in applicable policies and procedures. d) Engagement with the Central Bank 18. Firms did not have clearly defined procedures covering the various stages of the IQ process including initiation, compilation, completion, review, approval and submission of the IQ application. In addition, there was a lack of clarity in relation to what could be regarded as a material fact for inclusion in the IQ. 19. Firms did not have robust processes in place to identify, escalate and notify an appropriate individual or function, within the firm in a timely manner, of potential concerns regarding the fitness and probity of a CF or PCF holder. Additionally, there was a distinct lack of policies or procedures to support these escalations (i.e. investigation of concerns and the taking of timely action as appropriate) or to ensure timely notification of actions taken to the Central Bank. 20. Overall, the processes related to engagement with the Central Bank on fitness and probity issues, including IQ submission process, have not been adequately developed, documented or embedded. e) Role of the Compliance Function 21. The majority of firms had compliance frameworks, policies and procedures in place. There was a good understanding of fitness and probity obligations by the Compliance Function in a number of the firms inspected. However, in some cases there was an over reliance placed on the Compliance Function, thereby creating potential key person risk. 22. Many firms are not undertaking robust compliance testing of their fitness and probity processes and procedures. The fitness and probity process should be subject to periodic independent review by the third line of defence. If you need assistance with understanding or implementing the requirements, please contact the Team at CompliReg.

|

© CompliReg.com Dublin 2, Ireland ph +353 1 639 2971

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]