AuthorPeter Oakes is an experienced anti-financial crime, fintech and board director professional. Archives

January 2025

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

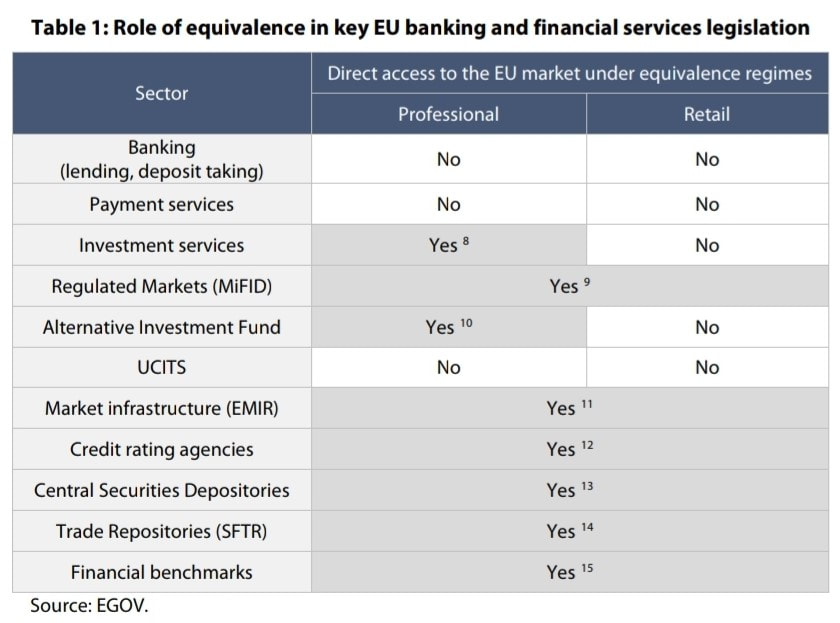

Some choice headlines in the papers about Brexit in the past week as we - according to Brexit Ireland's countdown to Brexit clock - just little more than 33 days before 11p.m. (UK time) on Thursday 31st December 2020 when the Brexit transition period ends with no deal on financial services in sight. This week sees the EU negotiating team returning to London after face-to-face talks came to end more than a week ago after Mr Bariner's team was hit by a case of Covid. They will be greeted by headiness such as: UK dismisses ‘derisory’ EU fishing offer ahead of last-ditch trade talks; Europe’s finance sector hits ‘peak uncertainty’ over Brexit; and The City braces for Brexit. There is no equivalence regime provided for within either EMD2 (electronic money institutions) or PSD2 (payments services institutions)! One thing we are still very surprised by is the many in #fintech, #techfin and indeed #finserv (and scarily their advisers) who think that recent news on 'equivalence' deals are applicable to all UK #finserv which passport across the European Union / EEA. The announcement on Monday 23rd November by the European Commission was simply and specifically about European regulators finalising a late change seeking to avoid chaos in £15tn of derivatives contracts held between UK and EU counterparties. Then on Wednesday 25th, they insisted outposts of EU banks in London would have to trade certain derivatives in the EU. Back in August 2020 the European Parliament reminded that "Equivalence decisions are a unilateral decision by the Commission. The Commission ultimately exercises its discretion as conferred upon it by the “empowerment” given in EU sectoral legislation.'' BUT MORE IMPORTANTLY "The Commission also enjoys discretion to withdraw equivalence decision. The equivalence frameworks in force do not provide as such specific procedures for monitoring, reviewing or amending equivalence decisions." There are no equivalence provisions in EU bank, payments nor electronic money directives, and the equivalence provision in MiFiD doesn't apply to retail investment services. See the below table on the 'Role of equivalence in key EU banking and financial services legislation' for confirmation. The upshot is that if you are a UK authorised payments institution or electronic money intuition, come Thursday 31st December 2020 when your ability to passport across the whole of European Economic Area comes to an end, so too does your business model unless you have obtained an authorisation in an EU/EEA state. There are are other options available but we'll leave that for another article. If you are a regulated fintech looking for a home post #brexit contact https://complireg.com/authorisations.html. Read our Fintech Authorisation Guides published jointly by CompliReg and Fintech Ireland on the authorisation process. And check out the 'Why Ireland for Fintech' brochure. Why Ireland for your regulated fintech?

“From January 1st, EU rules will apply to UK firms wishing to operate in the EU. UK firms will lose their financial passport: it’ll be anything but business as usual for them. This means they will have to adhere to individual home-state rules in each and every member state,” the official said. Further reading:

26 November 2020 - Move to EU or face disruption, City of London is warned

27 August 2019 - "Third country equivalence in EU banking and financial regulation"

29 July 2019 - Financial services: Commission sets out its equivalence policy with non-EU countries 12 July 2017 - "Third-country equivalence in EU banking legislation"

Back to Blog

Today, 17th November 2020, the Central Bank of Ireland released a Dear CEO Letter on "Thematic Inspections of Compliance by Regulated Financial Service Providers with their Obligations under the Fitness and Probity Regime". Readers are probably aware that the Central Bank issued a previous Dear CEO Letter on 8th April 2019 on "Compliance by Regulated Financial Service Providers with their Obligations under the Fitness and Probity Regime".

If you need assistance with understanding or implementing the requirements, please contact the Team at CompliReg.

What does the Dear CEO Letter of 17th November 2020 say? Background: The Central Bank undertook thematic onsite inspections across a sample of firms in the insurance and banking sectors [Ed- No reference to MiFID, payments, emoney, intermediaries nor the funds industry] in order to assess the level of compliance with the Fintess and Probity (F&P) requirements. This was on foot of its Dear CEO Letter on the topic of F&P back in April 2019. The inspections did not examine the fitness and probity of particular individuals, but rather evaluated the processes in place to manage compliance with the requirements of the F&P Regime. The inspections focused on the following areas:

The Central Bank towards the end of the letter reminds that the F&P Regime is a cornerstone of the regulatory framework in Ireland, applying not only to individuals but also firms. Firms must ensure that any individual who is engaged to carry out a CF role has the requisite fitness and probity to do so. The Central Bank’s Dear CEO letter of April 2019 emphasised the importance of compliance by firms and identified areas where compliance was inadequate. As is noted below and in the November 2020 letter, the Central Bank believes that the range of findings from thematic onsite inspections following the April 2009 letter "indicates that many firms do not have due regard to their obligations under the F&P Regime". The Central Bank is also concerned by the number of firms which did not take action, following the April 2019 letter, to perform a formal ‘gap analysis’ of their policies, processes and procedures. Its position seems clear "[i]t is wholly unacceptable that such shortcomings continue to exist in circumstances where the F&P Regime was introduced almost ten years ago." What did the Central Bank find?: In summary, the inspections highlighted a number of common issues and shortcomings, resulting in the release of the Dear CEO letter. The letter sets out key findings and observations from the inspections together with the expectations of the Central Bank, which it believes need to be brought to the attention of the wider financial services industry. Helpfully, the Central Bank also set examples of good practices which had been implemented in a number of firms (see Appendix 1 of the Dear CEO Letter November 2020 and set out below). A significant number of findings were identified in relation to the role of the Board, the conduct of due diligence and the outsourcing of CF roles. While not all of the issues outlined in the Dear CEO November 2020 letter arose in each firm inspected, the Central Bank reckons that they are representative of the findings across the sample of firms. What are the key points arising from the findings?: (a) role of the Board in the F&P Process:

(b) Conducting Due Diligence:

c) Outsourcing of Roles subject to the F&P Regime [Ed- the area of outsourcing is important for large, small, complex and non-complex firms alike]

d) Engagement with the Central Bank

e) Role of the Compliance Function

Conclusion of the Central Bank:

Appendix 1: Key Findings Identified by the Thematic Inspections a) Levels of awareness and understanding of the F&P Regime Role of the Board / Nomination Committee (“NomCo”) in Fitness and Probity Process 1. The level of awareness of fitness and probity obligations was weak throughout many of the firms, with Board awareness of its obligations particularly poor. 2. Board appointment procedures were generally not subject to the same level of scrutiny or formality as other CF and PCF appointments. In most cases, there was a lack of interview notes or suitability assessments available to support Board appointments. 3. In a number of instances there was no evidence of Board approval of the PCF appointment, Board approval of the appointment took place after approval by the Central Bank and/or there was no evidence of discussion or challenge by Board members of the proposed appointment. 4. Instances of the Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) screening potential Board candidates were noted in a small number of firms. This is inappropriate given the conflict of interests that arise as between the respective responsibilities of directors and the executive. 5. The quality of succession plans for the Board and executive team generally did not meet expectations. Anumber of these succession plans did not set out the skills, competencies and experience required for the various roles and/or how the proposed successor would demonstrate/acquire those. However, some firms had developed their own Board Skills Matrix, which set out the key areas of experience required. This matrix was used to identify gaps in the combined experience of the Board. Functional Responsibility for the F&P Regime 6. Management of the fitness and probity process varied significantly across the firms. Where there were clear, prescribed roles and responsibilities along with appropriate segregation of duties, the due diligence conducted in these firms was of a higher standard than those without clearly articulated and assigned responsibilities. 7. The quality of policies and procedures in relation to fitness and probity varied from firm to firm. Elements of good practice were observed in the form of ‘How To’ guides, establishment of Fitness & Probity Steering Committees, checklists, and clearly documented roles and responsibilities in relation to the fitness and probity process in the firm. However, good practice was not evident in most firms; the majority had disjointed processes that did not clearly outline the roles and responsibilities of the various functions performing fitness and probity related tasks. Analysis and Mapping of Roles 8. There were instances where no register of employees performing PCF or CF roles was maintained. In addition, the process of regular review of individuals whose role changed, resulting in their coming within the remit of the F&P Regime, was lacking. Good practices identified included a documented requirement to review the job description when a vacancy arises to determine if the role is CF or PCF in nature, and guidelines setting out the key principles and rationale for the general interpretation of the CFs across the firm. b) Conducting Due Diligence Initial Due Diligence 9. In the majority of the firms inspected, the initial due diligence undertaken was not sufficiently robust to evidence compliance with the requirements of the F&P Standards. Issues highlighted by the inspections included: a lack of evidence of academic qualifications; lack of references from previous employers; a notable absence of interview notes across the majority of firms inspected; and no evidence of a documented assessment as to the suitability of the candidate. 10. Issues were also identified in a number of instances with a lack of judgement searches, regulatory searches, directorship searches and adverse media searches, including adverse media searches regarding previous employers that could assist with identifying potential fitness and probity concerns to be examined further. 11. Firms assessed as performing better had defined processes in place for conducting initial due diligence, including documented policies and procedures; an understanding of the allocation of responsibilities among the various functions (e.g. Human Resources, Company Secretary and Compliance Function); performed due diligence searches and conducted and retained interview notes. Ongoing Due Diligence 12. Under Section 21 of the 2010 Act, firms are required to conduct due diligence on an ongoing basis to ensure that employees performing CFs continue to comply with the F&P Standards. 13. All firms had in place a requirement for each PCF and CF role holder to annually certify their compliance with the F&P Standards and their agreement to abide by the F&P Standards. An annual self-declaration by PCF and CF role holders is the minimum expected by the Central Bank. 14. However, the ongoing due diligence process in most firms is limited to the annual self-declaration. Firms should proactively conduct ongoing due diligence screening of staff to ensure there has been no change in circumstance that may affect the fitness or probity of the individual. In one firm they conducted ongoing due diligence searches on an annual basis for all PCF role holders and on a sample basis for CFs. c) Outsourcing of Roles subject to the F&P Regime 15. Where CF roles are outsourced to unregulated OSPs, the majority of firms had not, as part of their due diligence in appointing CF role holders, obtained the required documentation nor made any inquiries as to the OSP’s process for assessing fitness and probity. 16. Firms did not have a process whereby outsourcing arrangements were analysed to verify whether PCF or CF roles were being performed. This gives rise to the risk that relevant individuals at OSPs may not be identified and subjected to the F&P Standards. 17. In addition to obligations under the Central Bank’s F&P Regime, the Solvency II Regulations impose requirements on insurance firms with respect to the outsourcing of critical or important functions. Under these Regulations, firms are obliged to verify that all staff of the service provider who will be involved in providing the outsourced functions or activities are sufficiently qualified and reliable. There was generally a low awareness of Solvency II obligations in this regard and these had not been included in applicable policies and procedures. d) Engagement with the Central Bank 18. Firms did not have clearly defined procedures covering the various stages of the IQ process including initiation, compilation, completion, review, approval and submission of the IQ application. In addition, there was a lack of clarity in relation to what could be regarded as a material fact for inclusion in the IQ. 19. Firms did not have robust processes in place to identify, escalate and notify an appropriate individual or function, within the firm in a timely manner, of potential concerns regarding the fitness and probity of a CF or PCF holder. Additionally, there was a distinct lack of policies or procedures to support these escalations (i.e. investigation of concerns and the taking of timely action as appropriate) or to ensure timely notification of actions taken to the Central Bank. 20. Overall, the processes related to engagement with the Central Bank on fitness and probity issues, including IQ submission process, have not been adequately developed, documented or embedded. e) Role of the Compliance Function 21. The majority of firms had compliance frameworks, policies and procedures in place. There was a good understanding of fitness and probity obligations by the Compliance Function in a number of the firms inspected. However, in some cases there was an over reliance placed on the Compliance Function, thereby creating potential key person risk. 22. Many firms are not undertaking robust compliance testing of their fitness and probity processes and procedures. The fitness and probity process should be subject to periodic independent review by the third line of defence. If you need assistance with understanding or implementing the requirements, please contact the Team at CompliReg.

Back to Blog

Here's one for the #moneylaundering typology case studies for #MLROs as part of regulatory training requirements!

Relates to the collapse of major investigation into the Kinahan cartel and more than half a billion euros- particularly €500,000,000 stash of cars, properties & cash handed back to the accused by a Spanish judge after collapse of money laundering case. Can understand that staff and MLROs at financial institutions and other obliged entities which do a lot of the initial legwork in identifying suspicious transactions may feel underwhelmed (to say the least) when a case like this collapses. We should train on all types of cases, regardless if there is a criminal outcome or not. Staff (and boards) need to appreciate that not all suspicious transactions reports will 'result' in a criminal outcome, but that doesn't excuse obliged entities and their staff from complying with the legal requirement to report suspicious transactions. A skill MLROs and trainers need to focus upon is motivating staff, themselves and the senior executive to stay the course. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/peteroakes_moneylaundering-mlros-financialcrime-activity-6719937607700135936-jZUH #antimoneylaundering #financialcrime #mlros #suspicioustransactions #lawenforcement Check out the linkedin post with link to news article.

Back to Blog

ECB confident it can create a digital euro. With ECB officials concerned that the Chinese central bank is potentially a couple of years away from launching its own digital renminbi after it conducted large-scale experiments, it has identified several scenarios that would require it to launch a digital euro. Two scenarios are:

Either way, some serious #regtech and #suptech will be required. Despite a 55-PAGE REPORT, the question is whether the ECB can stay ahead of the rapidly changing world of #digitalcurrencies and #payments. Central bankers are increasingly interested in the relatively new world of digital currencies, particularly since Facebook announced a plan to launch one called Libra that has the potential to overhaul the way money works. ECB officials believe the Chinese central bank is potentially a couple of years ‘ away from launching its own digital renminbi after it conducted large-scale experiments. In an interesting development, Bloomberg reported on 1 October 2020, that the European Central Bank has applied to trademark the term “digital euro” as officials prepare to release an assessment of the benefits and drawbacks of creating a digital version of the currency. The application was filed on 22 September by the ECB’s legal representatives Bock Legal, according to the website of the European Union Intellectual Property Office. An ECB spokesman confirmed the filing. The ECB outlined potential scenarios “that would require the issuance of a digital euro”. These include higher demand for electronic payments that creates a greater need for a “risk-free digital means of payment”, as well as the potential that a cyber attack or pandemic disrupts the existing payment system and requires a digital euro to serve as a back-up. Another scenario is a further sharp drop in cash usage that leaves some people financially excluded. Finally, it examined the potential rapid adoption of other private or public digital currencies including those issued by foreign central banks that ‘could “threaten European financial, economic and, ultimately, political sovereignty”. The ECB said a digital euro “also poses challenges, but by following appropriate strategies in the design of the digital euro the Eurosystem can address these”. My Linkedin Post here Sources:

Back to Blog

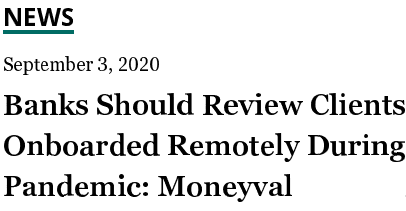

Peter Oakes, fintech and financial crime expert talks to Gabriel Vedrenne of ACAMS MoneyLaundering.com about European financial institutions that switched to onboarding all new clients remotely at the height of COVID-19 lockdowns should review their customer files to ensure that adequate due diligence was conducted as per the European anti-money laundering standard setter warned.

CLICK HERE

Back to Blog

"the settlement sends a strong message to industry that AUSTRAC will take action to ensure our financial system remains strong so it cannot be exploited by criminals" AUSTRAC 24 September 2020 Source: AUSTRAC

Press Release 24 September 2020 Westpac and AUSTRAC have today agreed to a AUD$1.3 billion dollar proposed penalty over Westpac’s breaches of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (AML/CTF Act). Westpac and AUSTRAC have agreed that the proposed penalty reflects the seriousness and magnitude of compliance failings by Westpac. The Federal Court of Australia will now consider the proposed settlement and penalty. If the Federal Court determines the proposed penalty is appropriate, the penalty order made will represent the largest ever civil penalty in Australian history. In reaching today’s agreement, Westpac has admitted to contravening the AML/CTF Act on over 23 million occasions, exposing Australia’s financial system to criminal exploitation. In summary, Westpac admitted that it failed to:

In reaching the agreement, Westpac has also admitted to approximately 76,000 additional contraventions which expand the original statement of claim. These new contraventions relate to information that came to light after the civil penalty action was launched last year and relate to additional IFTI reporting failures, failures to reasonably monitor customers for transactions related to possible child exploitation, and two further failures to assess the money laundering and terrorism financing risks associated with correspondent banking relationships. AUSTRAC’s Chief Executive Officer, Nicole Rose PSM said the settlement sends a strong message to industry that AUSTRAC will take action to ensure our financial system remains strong so it cannot be exploited by criminals. “Our role is to harden the financial system against serious crime and terrorism financing and this penalty reflects the serious and systemic nature of Westpac’s non-compliance,” Ms Rose said. “Westpac’s failure to implement effective transaction monitoring programs, and its failure to submit IFTI reports to AUSTRAC and apply enhanced customer due diligence in relation to suspicious transactions, meant AUSTRAC and law enforcement were missing critical intelligence to support police investigations.” Ms Rose said such a large number of breaches over several years was unacceptable and could have been avoided with better assurance and oversight processes to identify ongoing reporting failures. AUSTRAC works in partnership with the businesses we regulate through a comprehensive industry education program. “We have been, and will continue to work collaboratively with Westpac and all businesses we regulate to support them to meet their compliance and reporting obligations to ensure this doesn’t happen again in the future.” Westpac continues to partner with AUSTRAC to assist AUSTRAC and law enforcement agencies to stop financial crime, including as a member of AUSTRAC’s private-public partnership the Fintel Alliance. About AUSTRACAUSTRAC (the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre) is the Australian Government agency responsible for detecting, deterring and disrupting criminal abuse of the financial system to protect the community from serious and organised crime. Through strong regulation, and enhanced intelligence capabilities, AUSTRAC collects and analyses financial reports and information to generate financial intelligence. Learn more about AUSTRAC: https://www.austrac.gov.au/about-us/austrac-overview Media contactEmail: [email protected] Phone: (02) 9950 0488

Back to Blog

KBC Bank Ireland plc fined €18.3mn for regulatory breaches and being 'simply unconscionable.'24/9/2020 "Our investigation found KBC persistently refused to accept its failings despite having multiple opportunities to remedy the detriment that it was causing to its customers over an extended period. KBC’s actions in this regard, including the failure to adequately comply with the Stop the Harm Principles of the TME [Tracker Mortgage Examination], were simply unconscionable." Central Bank of Ireland 24 September 2020 Question: If KBC conducted itself in the manner contended by the Central Bank of Ireland, which KBC arguably agreed with (otherwise why would it have agreed with the view) why did the Central Bank afford KBC a discount of 30% on a fine which would have otherwise been €26,162,857? Source: Central Bank of Ireland

Press release – 24 September 2020 Enforcement Action Notice: KBC Bank Ireland plc reprimanded and fined €18,314,000 by the Central Bank of Ireland for regulatory breaches affecting tracker mortgage customer accounts On 22 September 2020, the Central Bank of Ireland (the “Central Bank”) reprimanded and fined KBC Bank Ireland plc (“KBC” or the “Firm”) €18,314,000 pursuant to its Administrative Sanctions Procedure (“ASP”) in respect of KBC’s serious failings to certain tracker mortgage customers holding 3,741 customer accounts from June 2008 to October 2019. KBC has admitted in full to 12 regulatory breaches. The Central Bank has imposed a fine at the highest end of its sanctioning powers, reflecting the gravity with which the Central Bank views KBC’s failures. The impact of KBC’s failings on its customers, which related to 3,741 accounts, was devastating and included significant overcharging and the loss of 66 properties. Additionally, KBC’s engagement and co-operation with the Central Bank’s Tracker Mortgage Examination (the “TME”) was deeply unsatisfactory. KBC caused avoidable and sustained harm to impacted customers due to the Firm’s unwillingness to acknowledge its failings until December 2017 and to take immediate action to apply the protections of the TME. Had KBC adhered to the TME guidelines sooner, without the need for significant and sustained Central Bank intervention, the harm to its customers – particularly incidences of property loss - would have been significantly reduced. The Central Bank determined that the appropriate fine was €26,162,857, which was reduced by 30% to €18,314,000 in accordance with the settlement discount scheme provided for in the Central Bank’s ASP[1]. This will be paid to the Exchequer[2]. This fine is in addition to the €153,524,363 that KBC has been required to pay to date in redress and compensation and account balance adjustments under the TME to its impacted tracker mortgage customers. The enforcement investigation, which was conducted in parallel with the TME, sought to determine how and why KBC failed to fulfil its obligations to their customers. The investigation also examined KBC’s failure to adhere to the Central Bank’s requirements under the TME. Over the course of 2008, tracker mortgages were becoming increasingly unprofitable for KBC, resulting in the withdrawal of the product by July 2008. The Central Bank’s investigation found that in doing so, KBC failed to treat its existing tracker mortgage customers fairly and put KBC’s financial interests above the protections their customers should have been afforded. In particular, KBC’s failures resulted from: (i) A proactive strategy to convert customers off their tracker rates: In 2008, KBC devised a strategy to permanently convert certain customers from their low-cost tracker rates. This applied to customers seeking fixed rates or interest only periods at a time when KBC knew that trackers were unprofitable for them. KBC failed to adequately warn the customers concerned that such amendments would result in the permanent loss of their tracker rates. The impact of this strategy was that certain customers, some of whom were already in financial distress, were required to make higher monthly mortgage repayments over the remaining term of their mortgages. This in turn increased the profit margin KBC made on these mortgages. (ii) Failure to adequately warn customers entering interest only or fixed rate periods that they would be unable to return to their tracker rates: At a time when KBC was withdrawing tracker products, it failed to provide customers with clear documentation and/or to provide customers with vital information that their request to fix their interest rate or move to an interest only period would lead to the permanent loss of their tracker interest rate. KBC also failed to warn customers seeking an interest only arrangement that they stood to pay more interest over the lifetime of their loan. (iii) Failure to adequately comply with the Central Bank’s Framework for the TME: KBC failed to adhere to the guidelines set out in the Central Bank’s TME Framework, requiring significant intervention from the Central Bank to ensure that all impacted customers were identified, redressed and compensated. (iv) Failure to adequately comply with the Stop the Harm Principles of the TME: From the outset of the TME in December 2015, KBC failed to take adequate steps to prevent customers from suffering any further harm or detriment pending the outcome of the TME review. This included failing to stop charging higher, incorrect rates of interest and failing to halt legal activity and loss of ownership of customers’ properties. Of the 66 properties referenced above that were lost as a result of KBC’s tracker mortgage failures, 39 of these could have been avoided had KBC implemented the Stop the Harm Principles immediately and as required. The Firm’s approach to, and implementation of, these protections was grossly inadequate. (v) Provided incorrect information to the Financial Regulator[3] in respect of KBC’s treatment of certain tracker customers: In 2009, KBC advised the Central Bank that customers who sought interest only arrangements did not lose their tracker rates for the remaining term of their loans. This was incorrect. As a result, certain interest only customers were denied redress and compensation and an account balance adjustment until identified as having wrongfully lost their tracker through the TME 8 years later. KBC only acknowledged that it had not treated these customers fairly following robust and sustained intervention by the Central Bank during the TME. (vi) Operational and systems failings: In addition, the investigation found that KBC had inadequate mortgage systems and/or operational controls in place to enable them to meet their regulatory and contractual obligations to certain customers. In total there were 12 separate regulatory breaches of the European Communities (Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts) Regulations 1995 (“1995 Regulations”), the Consumer Protection Codes 2006 and 2012 (“2006 Code” and “2012 Code” respectively). The Central Bank’s Director of Enforcement and Anti-Money Laundering, Seána Cunningham, said: “The Central Bank’s investigation into KBC has revealed a stark example of the very real harm caused to people when financial service providers fail to treat their customers fairly. By placing their own financial interests ahead of their customers’ best interests, KBC failed to adequately consider their obligations under the Consumer Protection Codes, which were put in place in order to protect customers in their dealings with financial service providers. The impact of KBC’s actions on their customers was devastating and avoidable. By overcharging customers over extended periods, KBC forced people into arrears, including certain customers whom KBC knew were already facing financial difficulties. Some customers suffered the most severe impact with 66 properties being lost by customers, 11 of which were family homes. Our investigation found KBC persistently refused to accept its failings despite having multiple opportunities to remedy the detriment that it was causing to its customers over an extended period. KBC’s actions in this regard, including the failure to adequately comply with the Stop the Harm Principles of the TME, were simply unconscionable. KBC’s initial review of their mortgage loan book during the TME identified only 93 impacted customer accounts. The total number of impacted customer accounts has since increased to over 3,700 but only following the sustained challenge and intervention of the Central Bank. We expect firms to engage in an open, timely and constructive manner with the Central Bank and to do the right thing by their customers, not because they are told to but because it is the right thing to do. KBC’s failures reinforce the Central Bank’s view that the financial services industry has a long way to go in breaking down the deep-set cultures that cause such terrible damage to people’s lives. Our message today is clear, and goes beyond the tracker mortgage related issues to all regulated firms: Firms should act in the best interest of their customers and consider their Consumer Protection Code obligations when making decisions that impact their customers. Where firms fail to do so, our response will be robust and the consequences will be serious.” Background to the investigation into KBC KBC Mortgage Bank (formerly IIB Homeloans Limited) is a credit institution and a regulated financial service provider. IIB Homeloans Limited applied for authorisation as a retail credit firm by the Central Bank in May 2008 following the enactment of legislation introducing the retail credit firm regime, thereby becoming subject to the Consumer Protection Codes from 1 June 2008. IIB Homeloans Limited subsequently obtained a banking licence from the Central Bank on 24 October 2008, at which time it officially renamed its operations in Ireland ‘KBC Mortgage Bank.’ In or around June 2009, KBC Mortgage Bank transferred its business to KBC Bank Ireland plc, amalgamating the businesses formerly conducted by IIB Bank plc and IIB Homeloans Limited/KBC Mortgage Bank. KBC introduced tracker mortgages to its range of products in 2003, ultimately withdrawing them from the market on 4 July 2008, as KBC viewed them as no longer profitable. In September 2015, the Central Bank notified lenders that it was developing the Framework for the TME, which was to be grounded on consumer legislation, including both the 2006 Code and the 2012 Code. In December 2015, the TME was established. Lenders were required to determine whether or not in all circumstances it had complied with its consumer protection regulatory obligations. The TME was designed to ensure that lenders met their consumer protection obligations by requiring lenders to: 1. Conduct a complete review of their tracker mortgage loan book to identify customers who may not have been treated fairly. 2. Take steps - pending the determination of impact under the TME - to (i) stop charging the incorrect rate of interest at the earliest possible time, (ii) halt all legal activity and (iii) ensure that customers did not lose ownership of their properties. The objective of this requirement was for lenders to take early steps to Stop the Harm, thus shielding potentially impacted customers from further harm and detriment. 3. Return impacted customers to the position they would have been in but for the tracker mortgage failings, which included, rate rectification or the option to return to a tracker rate. Furthermore, lenders were required to pay compensation commensurate to the harm caused to each customer given their specific circumstances. In early 2016, as part of its early engagement on the TME, the Central Bank notified KBC that it should consider whether the documentation provided to customers entering into an interest only or a fixed rate period may have led to an expectation that they could return to a tracker rate on expiry. When KBC failed to include those customers in the TME in September 2016, the Central Bank continued to challenge KBC’s assessment of whether particular groups of customers were impacted under the TME and therefore entitled to redress and compensation and have their account balance adjusted. KBC persistently refused to accept its tracker mortgage failings until December 2017, further evidencing KBC’s failure to put its customers first. KBC’s failings uncovered as part of the TME led to the commencement of the Central Bank’s enforcement investigation. Regulatory breaches KBC has admitted 12 regulatory breaches of the 1995 Regulations, the 2006 Code and the 2012 Code, which were identified during the Central Bank’s investigation. These breaches occurred as a result of the following:

Further detail of these failings is set out below. 1. A proactive strategy to convert customers off their tracker rate In 2008, KBC devised a strategy to permanently convert customers from their low-cost tracker rates, with the result that they were required to make higher monthly mortgage repayments over the remaining term of their mortgages and in turn increased the profit margin KBC made on the mortgage. At a time when KBC knew trackers were unprofitable, KBC implemented this strategy of seeking to permanently convert customers from their tracker rates through two separate direct mailings to customers in August and September 2008 (the “direct mailings”). KBC’s strategy was to convert its customers from their tracker rates to fixed rates, immediately increasing their margin, while ensuring that those mortgages would revert to standard variable rates and not a tracker on the expiry of the fixed rate period. Once this occurred, KBC could control the interest rate being charged. KBC failed to adequately warn those customers that they would not return to their tracker at the expiry of the fixed rate period. Following intervention by the Financial Regulator in 2008, KBC agreed to give the option to direct mailings customers who had switched from a tracker rate to a fixed to return to their tracker rates. Furthermore, during the course of 2008 and early 2009, KBC took the opportunity to move certain customers, some of whom were in arrears, from their pre-existing tracker rate when the customer requested to enter into or extended an existing interest only period. For example, in some circumstances, KBC required customers to switch to a standard variable rate to avail of the break in capital payments arising from the interest only arrangement, whereas in other instances, customers were required as a condition of approval for the interest only period to first enter into a fixed rate period that would not revert to their tracker on its expiry. In doing so, KBC failed to adequately warn those customers that they would not return to their tracker on the expiry of the interest only period. The resulting loss of the tracker rate invalidated the benefit to customers of availing of a temporary repayment break with the customers then making higher monthly mortgage repayments over the remaining term of their mortgages and increasing the profit margin KBC made on the mortgage. This practice continued into early 2009 in respect of certain interest only customers. Due to the fact that KBC provided incorrect information to the Financial Regulator in 2009 when challenged on this matter and failed to properly engage with the TME, the position of interest only customers was not fully rectified until late 2017, as explained in more detail below. This failure to rectify was despite the fact that KBC reviewed the position of some of their interest only customers’ accounts and customer documentation in 2011 as part of an internal review. KBC failed to adequately consider the impact of the strategy on their customers and their obligations under the 2006 Code. KBC has admitted that this strategy did not meet its obligation to act honestly, fairly and professionally in the best interests of its customers. The Central Bank also found that KBC failed to have and/or effectively employ necessary and/or adequate resources, procedures, and systems and control checks in place to ensure that it adequately considered its consumer protection focused obligations when taking strategic and financial decisions in relation to its tracker book. KBC has admitted breaches of the 2006 Code in respect of this behaviour, as follows:

2. Failure to adequately warn certain customers entering into interest only or fixed rate periods that they would be unable to return to their tracker rates The Central Bank found that KBC failed to comply with the requirements of the 2006 Code, the 2012 Code and the 1995 Regulations with regard to its obligation to ensure that documentation provided to customers at key points was clear and comprehensible and that key information was brought to their attention. These failures manifested in three distinct scenarios: Interest Only Customers Certain customers who sought forbearance on their mortgages through an interest only arrangement were impacted over the period from 19 June 2008 to 3 October 2018, many of whom were in financial distress and thus particularly vulnerable. The Central Bank found that contractual documentation that issued to certain interest only customers did not specifically refer to the rate that those customers would default to on maturity of the interest only period and thus it was not clear that those customers would lose their tracker rate for the remaining term of their mortgage. Certain customers lost their low cost tracker rates for the remaining term of their mortgage when they took up an interest only facility. Customers entering into a fixed rate using a Fixed Rate Instruction Form (“FRIF”) Certain customers were impacted when they sought to enter into a fixed rate period on their mortgage and completed a FRIF. Certain FRIF documents, when read in conjunction with other loan documentation, were unclear as to the rate to which the mortgage would default to at the end of the fixed rate period. These customers were therefore not clearly informed that they would not be able to return to their pre-existing tracker rate as a consequence of entering into the fixed rate period. Customers entering into a fixed rate after trackers were withdrawn Certain tracker mortgage customers who sought to enter into a fixed rate period after KBC had withdrawn tracker mortgages as a product offering were impacted. KBC failed to inform these customers in advance of fixing that they would no longer be able to avail of their tracker rate at the end of the fixed rate period, as trackers had been withdrawn from KBC’s product offering. KBC has admitted breaches in relation to its failures to warn customers as follows:

Certain of these breaches continued until the end of 2018, when KBC corrected the interest rates, paid redress and compensation and adjusted their account balances as part of the TME. 3) KBC’s failure to adequately comply with the Central Bank’s Framework for the TME The Central Bank’s Framework for the TME required lenders to conduct the TME and determine whether or not in all circumstances they had complied with their consumer protection obligations arising from a number of pieces of consumer legislation including the 2006 and 2012 Codes. The Framework also specified the manner in which lenders were required to conduct the TME, as follows: “When completing the Examination and when assessing compliance with regulatory requirements, the lender is to demonstrate that it is ensuring that customers’ interests are protected, that customers are being treated fairly and that it has considered customers’ reasonable expectations with regard to their entitlement to a Tracker Interest Rate, in the context of the information provided and the disclosures made by the lender to customers.” The Central Bank found that KBC’s approach to the TME evidenced a failure to comply with the consumer protection principles at the heart of the TME requirements that the Central Bank put in place in order to protect customers. KBC did not give adequate consideration to its regulatory obligations, to customer fairness or to the transparency of communications with customers, as required. Instead, KBC’s decision-making during the TME resulted in the identification of only a fraction of the customers rightly entitled to redress and compensation and have their account balance adjusted. In this regard, KBC did not deem interest only customers or customers who had received the FRIF as being impacted. KBC initially concluded that interest only customers had no entitlement to inclusion and that the Fixed Rate Instruction Form was clear. KBC took this position despite the Central Bank having raised concerns regarding both interest only and fixed rate customers at the outset of the TME. KBC ultimately conceded that these customers should be included in the TME in late 2017, following prolonged and consistent challenge from the Central Bank on these and other matters. From the commencement of the TME in 22 December 2015 to April 2019, KBC failed to:

each of which is contrary to the TME Framework which was designed to ensure the protection of impacted customers. KBC’s failure to adhere to the guidelines set out within the TME Framework resulted in the continued overcharging of certain customers’ accounts until KBC customers were put on the correct interest rates and paid redress and compensation and had their account balance adjusted. KBC has admitted breaches in respect of its failure to protect customers and apply the Central Bank’s Framework for the TME, as follows:

These breaches continued until KBC customers were put on the correct interest rates, paid redress and compensation and had their account balance adjusted. 4) Failure to adequately comply with the Stop the Harm Principles of the TME In June 2015, the Central Bank issued a letter to industry which set out the Central Bank’s regulatory expectations in respect of mortgage lenders, including those in respect of customers in financial difficulty. These regulatory expectations were grounded upon the 2006 and 2012 Codes. The purpose of this letter was to set out the outcomes and feedback from a themed inspection of mortgage lenders in respect of compliance with the Code of Conduct on Mortgage Arrears. The letter set out the regulatory expectations on mortgage lenders in respect of “Customer Impacting Issues for Borrowers in Financial Difficulty”. These regulatory expectations were the Stop the Harm Principles, which lenders were required to comply with to stop further detriment to potentially impacted customers. The Central Bank subsequently reiterated the Stop the Harm Principles specifically with regard to accounts within the scope of the TME, again grounded upon the 2006 Code and the 2012 Code. The core objective of the Central Bank’s work in the TME was to require lenders to seek to address the impact their actions had on impacted customers. To help achieve this aim, the Principles of Redress, including the ‘Stop the Harm’ Principles, required lenders to put in place, amongst other things, controls and measures to ensure that potentially impacted or impacted customers did not suffer any further detriment. These measures were designed to ring-fence and protect customers until such time as the lender could either satisfy themselves that the relevant customers were not affected or until such time as the lender had paid them redress and compensation and had their account balance adjusted. The ‘Stop the Harm’ Principles were designed to ensure that lenders ceased charging the incorrect rate at the earliest possible time, that lenders did not take steps in the legal process in relation to potentially impacted and impacted customers and that potentially impacted and impacted customers did not lose ownership of their properties. The Central Bank found that between December 2015 and September 2016, KBC failed to adequately implement the Central Bank’s Stop the Harm Principles with the procedures adopted failing to prevent further detriment from occurring to customers. KBC’s ‘Stop the Harm’ policy allowed it to take steps in the legal process, up to and including obtaining orders for possession in the Courts and appointing receivers over properties. This included instances whereby KBC authorised the progression of legal activities before they had made a final determination on the cohorts of customers that it considered ‘impacted’ under the TME. In September 2016, KBC incorrectly deemed customers who lost their tracker rates on taking up interest only arrangements as ‘not-impacted’ under the TME. Consequently, KBC removed the Stop the Harm protections for these customers. As of result of this action, 11 properties were unnecessarily lost by these customers. Finally, during the course of the TME, KBC failed to inform many customers seeking to sell, or otherwise dispose of their properties, including by way of assisted voluntary sale or surrender, that they may be impacted under the TME and may be entitled to redress and compensation and to have their account balance adjusted. Therefore, in some instances, the customer’s decision to dispose of their property was not fully informed. These failures resulted in additional and avoidable harm to certain customers and in some cases legal proceedings were progressed, up to and including loss of ownership. KBC has admitted breaches in respect of its failure to apply the Stop the Harm Principles, as follows

5) Provided incorrect information to the Financial Regulator Following media reports in 2009, which referenced that KBC were allegedly exploiting interest only customers by requiring them to move to a standard variable rate as a condition of taking up an interest only facility, the Financial Regulator sought clarification regarding the manner in which KBC treated those customers. KBC confirmed to the Financial Regulator that it did not remove tracker interest rates from both arrears and non-arrears customers who entered into interest only arrangements for the remaining term of their mortgages. This was not in fact the case as certain arrears and non-arrears customers had lost their tracker rates at the time. This investigation found that, through KBC’s failures to undertake proper due diligence and care in the gathering of information, KBC provided incorrect information thus misleading the Financial Regulator in 2009 in respect of the treatment of KBC’s interest only customers. This had far-reaching consequences for these customers. Having assured the Financial Regulator that these customers returned to their tracker rates on the expiry of the interest only facility, no further regulatory action was taken at that time. Consequently, customers who sought forbearance on their mortgage repayments continued to be charged higher rates of interest for the remaining term of their mortgages. The provision of this incorrect information to the Financial Regulator facilitated the persistent and ongoing breaches of the Consumer Protection Codes by KBC in relation to these customers until this issue was later identified and ultimately rectified under the TME. The Central Bank examined KBC’s treatment of interest only customers again in the context of the TME. At that point, the Central Bank became aware that KBC had provided incorrect information to the Financial Regulator in 2009. KBC ultimately conceded that interest only customers were impacted for the purpose of the TME in October 2017. This came only after robust challenge from the Central Bank regarding KBC’s initial decision in September 2016 to exclude these customers from the TME. Interest only customers finally received redress and compensation and had their account balance adjusted in late 2017, approximately 8 years following the incorrect information that had been provided by KBC to the Financial Regulator on the same issue. KBC has admitted breaches in relation to providing inaccurate information to the Financial Regulator, as follows:

6) Operational and systems failings During the course of KBC’s review of its tracker mortgage book and also within the TME, KBC identified a number of operational and systems failings which affected customers and resulted in, amongst other things, customers being placed on the incorrect interest rate; placed on the incorrect product type; provided with incomplete, inaccurate and unclear documentation; offered the incorrect tracker rate or not receiving appropriate information in relation to their entitlement or loss of entitlement to a tracker rate. In addition, due to operational and systems failings, KBC failed to comply with an undertaking given to the Central Bank in 2009 to return all of the direct mailing customers to their previous tracker rates. The investigation found that KBC had inadequate operational and systems controls in place to enable them to meet their regulatory obligations to certain tracker mortgage customers. Procedural and systems weaknesses, deficient processes, administrative errors including the failure to implement amendments to customer accounts in a timely manner, operational errors, reliance on standard documentation not tailored to the particular customers’ circumstances and reliance on manual interventions were all factors which contributed to KBC’s failings which occurred over an extended period of time. KBC has admitted breaches in relation to these operational and systems failings, as follows

Impacted numbers In summary, our investigation found that a total of 3,741 customer accounts were impacted as a result of KBC’s numerous failures over an extended period of time, with some customers being affected by more than one of the above issues. Penalty Decision Factors In deciding the appropriate penalty to impose, the Central Bank considered the ASP Sanctions Guidance issued in November 2019. The following particular factors are highlighted in this case: The Nature, Seriousness and Impact of the Contraventions

Aggravating factors

This enforcement action against the Firm is now concluded. This marks the completion of the second in a series of ongoing investigations which were commenced, and will therefore conclude, at different times. Notes to Editors 1. The Central Bank imposed a fine of €18,314,000 on KBC, which represents the maximum applicable penalty of €26,162,857 with a settlement discount of 30%. This fine is at the highest end of its sanctioning powers. The Central Bank’s ‘Outline of the Administrative Sanctions Procedure’ provides for an early settlement discount of up to 30% in order to promote early resolution of matters, which in turn leads to better utilisation of the resources of the Central Bank. For further information on the discount scheme, see the Central Bank’s ‘Outline of the Administrative Sanctions Procedure’, which is here. In October 2016, the Central Bank fined KBC €1,400,000 and reprimanded it for breaches of the Code of Practice on Lending to Related Parties 2010 and the Code of Practice on Lending to Related Parties 2013. Details of the Enforcement Action can be found here. 2. The Central Bank’s sanctioning powers were increased in 2013, pursuant to Section 68(b) of the Central Bank (Supervision and Enforcement) Act 2013. The maximum penalty which the Central Bank may now impose is €10,000,000, or an amount equal to 10% of the annual turnover of a regulated financial service provider, whichever is the greater. 3. This is the Central Bank’s 139th settlement since 2006 under its Administrative Sanctions Procedure, bringing total fines imposed by the Central Bank to over €123m, which total includes the fine imposed against Springboard Mortgages in 2016 and Permanent TSB plc in 2019 in respect of breaches of its obligations to tracker mortgage customers. This settlement also marks the 32nd outcome in respect of Consumer Protection Code breaches. 4. Funds collected from penalties are included in the Central Bank’s Surplus Income, which is payable directly to the Exchequer, following approval of the Statement of Accounts. The penalties are not included in general Central Bank revenue. 5. The Consumer Protection Codes 2006 and 2012 are available on the Central Bank’s website www.centralbank.ie or to download here and here. The 2006 Code ceased to have effect on 31 December 2011 and the 2012 Code came into effect on 1 January 2012. 6. The Tracker Mortgage Examination commenced in December 2015. The Examination required all lenders to review their loan book to ensure compliance with both regulatory and contractual requirements in relation to tracker mortgages. Where impacted customer accounts are identified, the Central Bank expects that those customers will receive redress and compensation commensurate with the detriment suffered and to have their account balance adjusted accordingly. Information on the Examination is available on the Central Bank’s website www.centralbank.ie or to download here. Further information: Media Relations: [email protected] / 01 224 6299 Ewan Kelly: [email protected] / 086 463 9652 [1] The Central Bank’s ‘Outline of the Administrative Sanctions Procedure’ provides for an early settlement discount of up to 30% in order to promote early resolution of matters, which in turn leads to better utilisation of the resources of the Central Bank. [2] All fines collected by the Central Bank are returned to the Exchequer. [3] The Financial Regulator was re-unified with the Central Bank on 1 October 2010.

Back to Blog

Access White Paper Here

In the not too distant past, senior management within financial institutions may have regarded failure to comply with anti-money laundering (AML) requirements as low impact. The 2007/8 financial crisis as well as subsequent scandals in financial services have shown the error of this approach. When it comes to AML, the current COVID-19 crisis may pose an evolving and unpredictable threat. To avoid a repetition of the previous mistakes, financial institutions must now put into practice lessons learned from the past; the most urgent one in my book, is that institutions should be adopting a culture of compliance with a ‘live and breathe’ approach to regulatory requirements. In a recent article in the Economist, Jürgen Stock, secretary-general of Interpol, was quoted as saying that COVID-19 may create the ideal conditions for the spread of serious, organised crime. Moreover, Mr. Stock believes that the immanent global economic depression will offer these criminals a chance to extend their reach deep into the legitimate economy. As COVID-19 motivates criminals to evolve their operations, those responsible for stanching the flow of ill-gotten gains into the legitimate economy must stay one step ahead; and this includes financial institutions with their AML obligations. I recently published a white paper on the lessons to be learned from the last financial crisis. For those interested in how a culture of compliance can address complex misconduct relating to AML, this paper is well worth a read. Through reviewing a number of high-profile case studies, I come to the conclusion that at the heart of many AML failures is an institutional culture that treats AML training and procedures as merely means to meet regulatory requirements. The case studies show that these banks failed to ‘live and breathe’ regulatory requirements and that the institutional culture prioritised compliance as merely a tick the box exercise, thereby failing to communicate to employees the priority of compliance and the flexibility of decision making and behaviour that may be necessary to fulfil their AML requirements. Culture is a complex issue. For those interested in how RegTech can enable an examination of institutional culture, through diagnostic tools, the white paper is a must read. In the paper, I explore how The Mizen Group, a RegTech firm based in New York, has developed a suite of tools to help boards and their compliance officers assess the extent to which their institution demonstrates the characteristics of an organisation with a strong compliance culture. The financial crime threats posed by COVID-19 mean that now is the time to commit to a culture of compliance from the ground up. Launderers and criminals are capitalising on the chaos created in the wake of the pandemic and are seeking ways to out-manoeuvre the financial institutions who are generally playing catchup. In response, board of directors and executive management need to be proactive and flexible in their thinking and develop a ‘live and breathe compliance’ mentality. This will only occur in a healthy compliance culture, wherein employees are empowered to internalise the importance of complying for the right reasons. The first step towards the goal of a healthy compliance culture might be employing tools like Mizen’s innovative culture diagnostics to assess their institutions’ cultural strengths and weaknesses. Feel free to contact the RegTech experts at The Mizen Group for further information. Access White Paper Here This blog also appears at Peter Oakes' blog

Back to Blog

Not long after the European Union’s top court ordered Ireland on 16 July 2020 to pay a lump sum of €2 million to the European Commission for Ireland's failure to implement regulations aimed to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing, a new law aimed at strengthening existing Irish anti-money laundering legislation and giving effect to provisions of the 5th EU Money Laundering Directive has been approved by the Cabinet of the Irish Government.

On Monday 10th August 2020, the Cabinet has approved the publication of the Criminal Justice (Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing) (Amendment) Bill 2020. This follows the signing into law by the President of Ireland on 5th May 2020 of the earlier Criminal Justice (Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing) Act 2010 (Act 6 of 2010) [previously known as the Criminal Justice (Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing) Bill 2009 (Bill 55 of 2009)]. If you need advice on the new Bill or your existing regulatory compliance obligations, get i touch with Peter Oakes here at at CompliReg. Useful Links:

The Minister for Justice and Equality, Helen McEntee T.D., has received Cabinet approval for the publication of the Criminal Justice (Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing) (Amendment) Bill 2020. The Bill transposes the criminal justice elements of the 5th EU Money Laundering Directive and strengthens existing legislation. Upon announcing the new Bill, the Minister McEntee said, "I look forward to bringing this legislation before my colleagues in both Houses, and anticipate that this Bill will receive broad, cross-party support." What does the Bill contain? The Bill includes provisions to:

The Minister also noted that: "This Bill is an important piece of legislation for tackling money-laundering. The reality is that money laundering is a crime that helps serious criminals and terrorists to function, destroying lives in the process. Criminals seek to exploit the EU’s open borders, and EU-wide measures are vital for that reason. This new legislation also includes a number of technical amendments to other provisions of Acts already in force." While the Bill transposes certain elements of the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, the Department of Finance is also engaged in giving effect to certain provisions of the Directive, including those relating to:

The Minister for Finance (Paschal Donohue, T.D.) has also secured Government Approval to bring forward amendments in respect of the regulation of Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs). The amendments will ensure that the necessary registration and fitness and probity regime, required by 5AMLD for virtual asset service providers, become statutory requirements. Amendments will also address Ireland’s international obligations, relating to a robust regulatory framework for new technologies, new products and new practices, as identified by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Back to Blog

Irish Bank, Bank of Ireland, fined €1,660,000 over cyber-fraud and misleading the Irish Regulator28/7/2020 Enforcement Action Notice: The Governor and Company of the Bank of Ireland fined €1,660,000 and reprimanded by the Central Bank of Ireland for regulatory breaches causing loss to a client and for misleading the Central Bank in the Central Bank in the course of the investigationSummary:Here's a blueprint for inviting an enforcement action for cyber-fraud & misleading your regulator arising from Bank of Ireland's fine €1,660,000 announced today. [Linkedin Post Here] What did Bank of Ireland do wrong?: 1) failed to implement sound administrative procedures & internal control mechanisms in respect of third party payments. 2) failed to introduce adequate organisational arrangements around third party payments to minimise the risk of loss of client assets as a result of fraud. 3) failed to establish, implement & maintain systems & procedures adequate to safeguard the security, integrity & confidentiality of client bank account details. 4) failed to establish, implement & maintain adequate internal control mechanisms designed to secure compliance with its reporting obligations pursuant to Sec. 19 of the Criminal Justice Act 2011. 5) failed to monitor adequacy & effectiveness of the measures & procedures put in place & the actions taken to address any deficiencies in respect of third party payments. 6) failed to be open & transparent, having the effect of misleading the Central Bank in the course of the investigation. Facts of Matter according to Central Bank of Ireland:On 27 July 2020, the Central Bank of Ireland (the Central Bank) reprimanded and fined The Governor and Company of the Bank of Ireland (BOI) for five breaches of the European Communities (Markets in Financial Instruments) Regulations 2007 (the MiFID Regulations) committed by its former subsidiary, Bank of Ireland Private Banking Limited (BOIPB). BOI has admitted the breaches, which vary in length from one to ten years.

In line with its published Sanctions Guidance, the Central Bank has determined the appropriate fine to be €2,370,000, which has been reduced by 30% in accordance with the settlement discount scheme provided for in the Central Bank’s Administrative Sanctions Procedure. The Central Bank’s investigation arose from a cyber-fraud incident that occurred in September 2014 (the Incident). Acting on instructions from a fraudster impersonating a client, BOIPB made two payments to a third party account totalling €106,430: one from a client’s personal current account, the other from BOIPB’s own funds. BOIPB immediately reimbursed the client. During a Full Risk Assessment of BOIPB in 2015, the Central Bank discovered a reference to the Incident in an operational incident log. BOIPB had not reported the cyber-fraud to An Garda Síochána, and only did so at the request of the Central Bank over one year after the Incident. The Central Bank’s investigation found serious deficiencies in respect of third party payments, including:

BOIPB’s failure to be open and transparent had the effect of misleading the Central Bank in the course of the investigation. BOIPB failed for a period of 19 months to disclose to the Central Bank an internal report, commissioned following the Incident, which identified ongoing systemic control failings in the processing of third party payments. During that same period, BOIPB strenuously denied the existence of any such failings to the Central Bank in response to the investigation. BOIPB’s conduct materially added to the time it took to investigate this case. This is one of two aggravating factors in this case; the other being the excessive amount of time it took BOIPB to fully remediate the relevant deficiencies. Remediation in relation to third party payment processes took place in February 2016, 17 months after the Incident, and then only following the Central Bank’s intervention. In August 2016, the Central Bank determined that a Risk Mitigation Programme (RMP) relating to third party payment processes was completed. The Central Bank’s Director of Enforcement and Anti-Money Laundering, Seána Cunningham, said: “The Central Bank has a clear expectation that firms are alert to the real and increasing risks from cyber-fraud to the security of their clients’ deposits and confidentiality of their clients’ financial information, and put in place appropriate safeguards to protect their clients accordingly. This is the second time the Central Bank has imposed a sanction on a firm where a client has suffered a loss from cyber-fraud as a direct result of the firm’s regulatory failings. BOIPB’s failure to put appropriate safeguards in place exposed BOIPB and its clients to the serious and avoidable risk of cyber-fraud. That risk crystallised twice. BOIPB then failed to report the cyber-fraud to An Garda Síochána, which is a serious matter. Reporting illegal activity is essential in the fight against financial crime. This case should serve to highlight to all firms the importance of ongoing vigilance in the area of cyber security. The Central Bank expects all firms to consider, identify and manage operational and cyber risks and ensure that their staff receive appropriate training tailored to the risks associated with their duties and responsibilities. The Central Bank expects pro-active engagement from regulated entities – that extends from self-reporting through remediation and full cooperation with the investigation. The excessive time taken by BOIPB to remediate identified deficiencies and the failure to be fully transparent and open in the context of the Central Bank’s investigation were aggravating features in this case.” BACKGROUND Founded in 1989, BOIPB was first authorised as a “section 10 investment business firm” under the Investment Intermediaries Act, 1995 (the 1995 Act) on 26 May 2000. This authorisation was subsequently transferred to an authorisation under the MiFID Regulations on 1 November 2007. At the time of the cyber-fraud, BOIPB was an independently regulated MiFID firm and its primary activity was to provide investment services to high net worth individuals who had investable assets in excess of €1,000,000. In addition, BOIPB provided a full range of banking services to its clients (lending, deposit taking and day-to-day current account banking) as a deposit agent of BOI. Since 1 September 2017, BOIPB is no longer a MiFID firm and is now a business unit within the Retail Division of BOI. The unit retains the name Bank of Ireland Private Banking as a trading name of the Governor and Company of the Bank of Ireland. Its services are authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland under the licence of BOI, a regulated financial service provider for the purposes of the Central Bank Act 1942. BOIPB’s audited financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2016, the last year it existed as a separate entity, reported operating income of €19,867,000. THE CYBER-FRAUD Third party payment instructions were processed by BOIPB with particular reference to a procedure called the Third Party Payments Procedure (the TPPP), which outlined steps to be followed to verify a client’s identity before processing a third party payment instruction. BOIPB processed two separate payment instructions received in September 2014, purportedly from a client (the Client), which in fact were sent by a cyber-fraudster (the Fraudster) who had hacked the Client’s e-mail account. This led to two transfers totalling €106,430 to be transmitted to a corporate bank account at a UK bank. The first transfer was drawn from the Client’s current account, and the second transfer was drawn, at the instigation and authorisation of BOIPB, from BOIPB’s suspense account because the payment from the Client’s deposit account was rejected due to insufficient funds. The Client made contact with BOIPB and notified it of the fraud on 30 September 2014, on receipt of an e-mail from BOIPB indicating recent communications (which were unfamiliar to the Client). The Client was immediately reimbursed by BOIPB. To facilitate the instructions received from the Fraudster, BOIPB staff, in breach of BOIPB’s policies and procedures:

The Fraudster used the following tactics:

PRESCRIBED CONTRAVENTIONS The Central Bank investigation identified the following contraventions: Contravention 1 BOIPB breached Regulation 33(1)(f)(i) of the MiFID Regulations between 1 November 2007 and August 2016 by failing to implement sound administrative procedures and internal control mechanisms in respect of third party payments. The Central Bank’s investigation found that the TPPP was wholly inadequate for the purposes of safeguarding client deposits when processing third party payments. In particular, key procedural, security and authorisation steps were not outlined in the document. Staff did not receive adequate training on the processing of third party payments to ensure they were fully aware of how to safely process these payments. Contravention 2 BOIPB breached Regulation 160(2)(f) of the MiFID Regulations between 1 November 2007 and August 2016 by failing to introduce adequate organisational arrangements around third party payments to minimise the risk of loss of client assets as a result of fraud. The serious weaknesses in the process around third party payments, which had existed for some time, should have been known to management through proper governance, oversight and monitoring. There was no monitoring of third party payments by the first or second lines of defence. Furthermore, the recommendations of the first internal report commissioned by BOIPB in relation to this matter, dated December 2014, were not acted on. Similar weaknesses were identified in a second internal report in January 2016. Remediation of the issues identified in both reports did not take place until February 2016. Contravention 3 BOIPB breached Regulation 34(3)(a) of the MiFID Regulations between 1 November 2007 and 2 January 2018 by failing to establish, implement and maintain systems and procedures adequate to safeguard the security, integrity and confidentiality of client bank account details. The investigation found that for the purposes of customer service, BOIPB staff frequently engaged with private clients through e-mail. E-mail communication, because it is more vulnerable to infiltration by fraudsters than other forms of communication, needs to incorporate additional checks before being acted upon. By failing to identify and provide for this, BOIPB failed to safeguard the security, integrity and confidentiality of information relating to client bank accounts. Contravention 4 BOIPB breached Regulation 34(1)(c) of the MiFID Regulations between 30 September 2014 and 16 December 2015 by failing to establish, implement and maintain adequate internal control mechanisms designed to secure compliance with its reporting obligations pursuant to Section 19 of the Criminal Justice Act 2011. BOIPB reported the Incident to its Group Financial Crime Unit (GFCU) on 1 October 2014. GFCU, on behalf of BOIPB, did not report the Incident to An Garda Síochána until December 2015, on the instigation of the Central Bank. Contravention 5 BOIPB breached Regulation 35(2)(c) of the MiFID Regulations by failing to comply with Regulation 34(4) between November 2013 and December 2016 because, for that period, BOIPB’s Compliance function failed to monitor, and on a regular basis to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the measures and procedures put in place and the actions taken to address any deficiencies in respect of third party payments. The TPPP included a requirement that ad-hoc monitoring of third party payments be carried out by the Compliance function. The investigation found that throughout the period November 2013 to May 2016, no ad-hoc monitoring of third party payments was in fact carried out. This failure persisted despite two internal reports highlighting the absence of monitoring and the systemic non-adherence to the TPPP. BOIPB’S RESPONSE TO THE CYBER-FRAUD AND REMEDIATION The Central Bank expects firms to promptly remediate known deficiencies in their procedures and internal control mechanisms. BOIPB failed to do so. Following the Incident, BOI Group Internal Audit function (GIA) investigated how it had occurred. GIA produced their findings in a report in December 2014, which pointed to systemic failings in the processing of third party payments. GIA strongly recommended that BOIPB carry out sampling to verify the authenticity of other “high-value interpays”. BOIPB failed to do this. GIA further recommended, that, at a minimum, the procedure in place relating to third party payments should be enhanced to clarify roles and responsibilities for authenticating and approving third party payments. Again, BOIPB failed to do this. The procedure remained unchanged until February 2016. In March 2015, BOIPB commissioned a further internal review, this time by BOI Retail Business Assurance (RBA) centred on BOIPB’s procedures for processing third party payments. Separately, following the Full Risk Assessment (the FRA) conducted in 2015, the Central Bank informed BOIPB that improvements in relation to third party payment processes would be part of the subsequent RMP arising from the FRA as the process in place was “not robust enough”. The RMP was issued in February 2016, which set out the Central Bank’s expectations in relation to the actions needed to improve the third party payment process. RBA issued its findings in draft to BOIPB in January 2016 (the RBA Report). Following an assessment of a sample of third party payment records, RBA concluded that the same issues identified in December 2014 persisted, namely that client identification questions were not consistently being asked of clients as well as other deficiencies in the third party payment process. BOIPB updated and revised the TPPP in February 2016. The RBA Report was signed-off in June 2016. In August 2016, the Central Bank determined that the full RMP was completed. BOIPB’S COOPERATION WITH THE CENTRAL BANK The Central Bank expects regulated entities to cooperate in an open manner at all times and to respond to requests promptly, effectively and accurately. When the Central Bank’s investigation commenced in February 2016, BOIPB possessed the RBA Report which contained highly critical findings in relation to the processing of third party payments. As such, it was highly probative to the Central Bank’s investigation. The Central Bank issued a request for records in February 2016. BOIPB should have provided a copy of the RBA Report when it responded to this request in April 2016. BOIPB failed to do so, instead it included one vague narrative reference to a risk assessment of banking activities (making no reference to a “report” or the fact that it related to third party payments specifically) within a document accompanying the records it supplied in response to the Central Bank’s request. BOIPB disclosed the RBA Report to the Central Bank 19 months after the commencement of its investigation in response to a Central Bank statutory request explicitly requiring production of the record BOIPB had described as a “risk assessment”. It was only when the document was disclosed and reviewed that its true nature and content became apparent to the Central Bank. The Central Bank conducted lengthy enquiries as to the circumstances around BOIPB’s failure to promptly disclose the RBA Report and the following arose:

SANCTIONING FACTORS In deciding the appropriate penalty to impose, the Central Bank considered the ASP Sanctions Guidance issued in November 2019. The following particular factors are highlighted in this case. The Nature, Seriousness and Impact of the Contravention

The Conduct of the Regulated Entity after the Contravention Aggravating

Other Considerations

The Central Bank confirms that the investigation is now closed. NOTES

Further information: Media Relations: [email protected] / 01 224 6299 Ewan Kelly: [email protected] / 086 463 9652 |

© CompliReg.com Dublin 2, Ireland ph +353 1 639 2971

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]

| www.complireg.com | officeATcomplireg.com [replace AT with @]